Following the international success of his latest documentary Of Caravan and the Dogs, the Oxford Political Review spoke with exiled Russian director Askold Kurov from Berlin about the making of his film, the collapse of independent news in Russia as the country prepared for war in Ukraine, and the gloomy prospects for change in a country with a practiced history of civil repression.

Of Caravan and the Dogs provides a rare and intimate insight into Moscow’s opposition circles in the days running up to the Kremlin’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Filmed between November 2021 and January 2023, Kurov and his co-director, who resides in Russia and has remained anonymous, chronicle the death of the last remaining vestiges of opposition media in Russia. While the world’s attention was focussed, rightfully, on Russian military force massing on Ukraine’s borders, Kurov’s film takes his viewers back to Moscow and its small circles of opposition figures, desperate to provide impartial reporting on Putin’s so-called ‘special military operation’. In its most candid moments, Kurov’s film is a portrait of Russia’s opposition coming to terms with its collective failure to hold its government to account for unleashing the biggest war on European soil since the Second World War. It reminds its audience that many Russian citizens do not support Putin’s war but feel paralysed by the dire risks of publicly voicing dissenting opinion.

Through Kurov’s deep connections to opposition news outlets like Novaya Gazeta and the human rights organisation Memorial, both Nobel Peace Prize recipients, the Russian director provides a firsthand account of the extreme stranglehold Putin’s regime has established on narratives which risk challenging the Kremlin’s official lines of communication. Kurov’s documentary has screened at the Sheffield International Documentary Festival, Munich International Documentary Festival, Krakow Film Festival and CPH: DOX. The trailer for the film can be viewed here.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Jack Burling Nebe (OPR): Let us begin with the idiom you use to bring the film into focus: the caravan and the dogs, or the more widely used version ‘the dogs bark but the caravan goes on’. Could you explain why you chose this to frame your film?

Askold Kurov (AK): The idiom comes from the film itself. When Dmitry Muratov (Novaya Gazeta’s Editor in Chief) accepted the Nobel Peace Prize in 2021, he said that in Russia the authorities often say, ‘the dogs bark but the caravan goes on’, meaning that journalists speak loudly about injustices, but in reality, it does little to change the behaviour of the caravan.

However, Muratov thinks the real meaning of the idiom is different, that there is another way to understand the saying. Muratov thinks that the caravan goes on because of the barking of the dogs. It is the barking of the dogs that defends the caravan, meaning our society, from the predators, from its harsh environment. Under this understanding, Muratov thinks it is the barking of the dogs that drives forward the caravan. And it is the mission of journalism and human rights activists to bark, to protect society from political catastrophe.

OPR: When we spoke previously, you mentioned that the original idea for the film was entirely different. Could you explain what your original vision was to our readers?

AK: Yes, the initial idea was to make a film with Muratov and the Novaya Gazeta team dedicated to the seldomly talked about Philosophers’ Ships incident, which in 2022 had its 100 year anniversary. In 1922, more than two-hundred public intellectuals were deported from the Soviet Union under the direct orders of Lenin. These people were mostly writers, philosophers, thinkers, and scientists. The Soviet government got rid of them because they were in the opposition and they were dissidents. Trotsky, one of the political leaders of the time, explained the decision by saying that ‘we had no grounds to kill them but no room to tolerate them’.

Now, 100 years later, we found the situation repeated. We do not have any ships, but we now have these new foreign agent laws from the Kremlin. So that was the original idea for the film. But then things started to change so quickly and we decided to change the focus of the film.

OPR: I would like to talk about the risks of making this film as a Russian. I am curious if, when you were filming with your co-director, you had any conversations about whether the situation had become too dangerous to actually proceed with making the film?

AK: First of all, I should mention that my co-director (Anonymous 1) will remain anonymous because they have chosen to stay in Russia in order to continue our work. Yes, it is of course risky for them to be involved in this film as they continue risk being jailed.

In terms of what the filming was like, we tried to follow the deliberations of our ‘characters’ as accurately and faithfully as possible. But the situation was developing rapidly. Every day, every hour, something was happening. We were following Novaya Gazeta, TV Rain, and Memorial mostly. As documentarians, it was an incredible situation because we had credibility with these groups and they considered us reliable persons so they gave us access to everything.

But after we finished filming and started editing, we faced questions of censorship and self-censorship. Many of our characters, maybe half of them, are still in Russia and we cannot put them in danger. The risks are high – Novaya Gazeta has had their journalists murdered and imprisoned before. We had to carefully review all the material we included in the final film with a team of lawyers who are experts in Russia’s new foreign agent laws.

But before that, we made a final decision of making a film as though we didn’t have any censorship at all – let us be as free as possible. I hope one day we will be able to release that full version, with no self-censorship.

OPR: You chose to end the film with a segment from Yan Rachinsky’s Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech. There Rachinsky, a human rights campaigner and co-chair of Memorial, argues against the notion of collective responsibility, asserting rather that ordinary Russians need to take personal responsibility for the Kremlin’s war of aggression in Ukraine. Do you think questions of responsibility for Putin’s war are important to Russian society? Why did you choose to end the film with Rachinsky’s remarks?

AK: The idea was to close the circle between the two Nobel Peace Prize speeches: Muratov’s 2021 ‘dogs and caravans’ speech and Rachinsky’s 2022 acceptance speech. For me, a significant piece of history happened between these two speeches. In 2021, we see Muratov trying to warn us about what is about to happen in Russia. He is trying to warn us about freedom of speech; that society is being prepared for a war with Ukraine; and that the idea of war with Ukraine is becoming less impossible. When he said this, it sounded unbelievable. Yes, the possibility of war was discussed widely in both Russian and international media, but everyone was saying that this was just Putin’s game and that he actually only wanted a deal with the West. Muratov is making the case that it is the job of Russia’s opposition media and its journalists to try to protect society by speaking out with their ‘barking’.

At the end of the film, we see what has happened. We, the opposition, could not protect society enough. We could not stop the war and civil society could not do enough to resist Putin’s regime. I think this is why Rachinsky talks about this – he is warning us about the future of Russian society. That we will need to talk about our failures: our collective responsibility, collective guilt, and personal responsibility for what has happened and what is happening in Ukraine. Why could we not do enough to defend our rights and our peace? What can we do now?

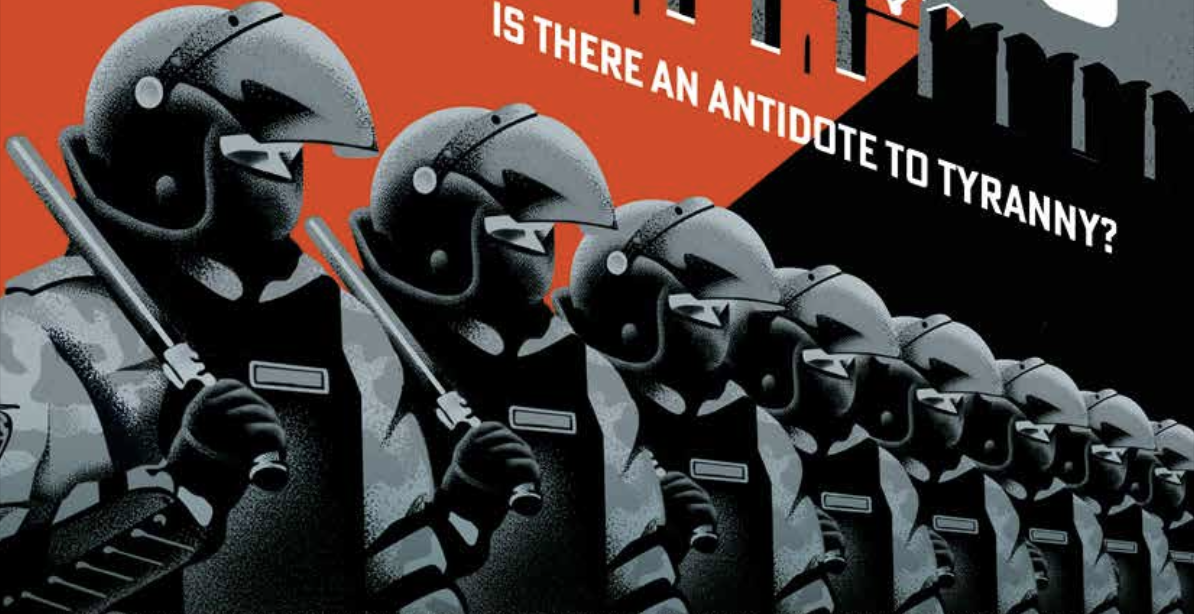

Image Credit: Of Caravan and the Dogs press package