In the past decade, scepticism regarding whether international law is considered law has been on the rise. Sceptics who operate under John Austin’s ‘Command Theory of Law’ argue that international law is not a true legal system in the sense that states do not always comply with it, and there are not sufficient threats of punishment for failure to comply. Two considerations challenge the strength of this argument. First, and most importantly, the question of whether international law is law should not consider whether states implement rulings or not. Second, since sceptics define international law using theoretical criteria classically applied to domestic law, it is essential to recognise that no domestic law in any constituency enjoys absolute compliance, highlighting the unfeasible standard to which they hold international law to. It is equally unfair to judge international law as theoretically invalid on the grounds of imperfect practical implementation, as it would be to judge domestic law theoretically invalid on similar grounds. The validity of a legal system is not dependent upon universal compliance with its rules.

H. L. A. Hart’s book, The Concept of Law, is widely regarded as the most influential work of legal philosophy in the twentieth century. More specifically, it provides a foundational basis for understanding how international law is considered law. Hart states that ‘law [is] the union of primary and secondary rules.’ Hart defines primary rules of obligation as those ‘that guide behaviour by imposing duties or conferring powers on people.’ Primary rules impose obligations when they meet the following three characteristics: (1) there must be an insistent demand for conformity with meaningful social pressure on any actor who does not wish to conform; (2) the rule must be seen as necessary to maintain some aspect of social life; and lastly, (3) the rule must sometimes require the actor to act in a way that contradicts their desires, in order to benefit another.

Hart defines secondary rules as those ‘that provide for the identification, alteration, and enforcement of the primary rules.’ There are three types of secondary rules, known as rules of recognition, change, and adjudication. First, the ‘rule of recognition,’ — established in any form — which determines an authoritative list of primary rules and gives legal validity to such primary rules, solving the ‘uncertainty’ of the rules. In other words, the rule of recognition provides a bridge between primary and secondary rules. Second, the ‘rule of change,’ which allows an authoritative body to introduce, amend, or eliminate primary rules, solving the ‘static’ form of the rules in terms of potential inflexibility. Third, the ‘rule of adjudication,’ which allows an authoritative body to assess the compliance with such primary rules, solving the ‘inefficiency’ of the regime of the rules.

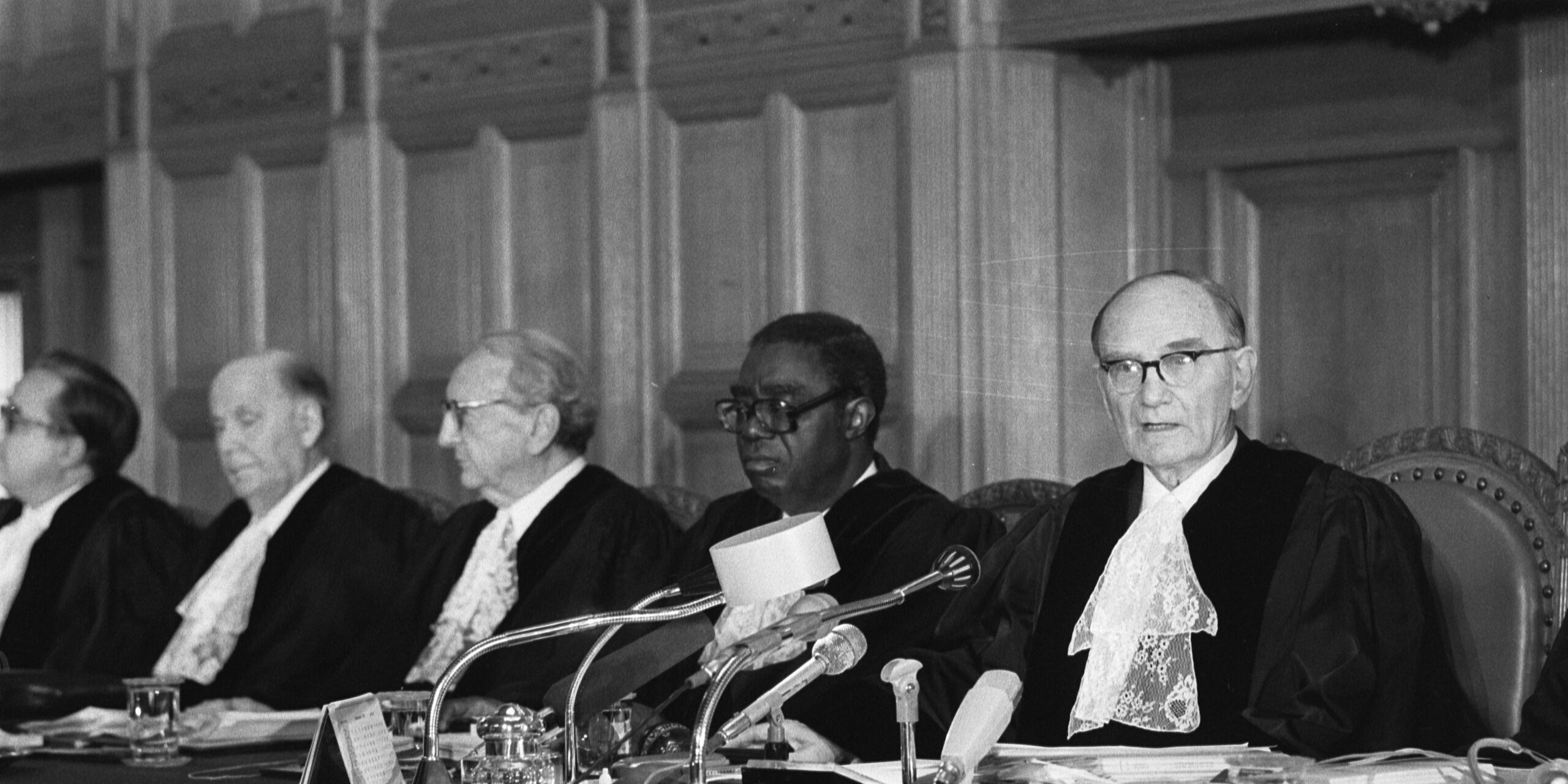

Considering the language of Hart’s Concept of Law, the question that arises is: How does international law embody Hart’s Concept of Law, specifically in demonstrating an observable union of primary and secondary rules? This question has been answered by previous legal scholars who have established that international law does have secondary rules. For example, some suggest that Article 38(1) itself of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) Statute is the secondary rule of recognition in international law, providing legal validity to the primary rules of obligation. Similarly, others argue that international lawyers in international tribunals and the United Nations (UN) Security Council act as the rule of change in international law by creating and altering rules. Still others state that the ICJ and other authoritative international and regional courts constitute the rule of adjudication in international law by assessing the compliance of rules.

Correspondingly, the four official sources of international law stipulated in Article 38(1) can act as the primary rules, which generate obligations upon states. However, there are no available accounts that demonstrate how each individual source in Article 38(1) acts as a primary rule that generates obligations upon states. As a result, by using Hart’s Concept of Law, this piece attempts to rejoin sceptics by explaining how international law is considered law. In other words, this involves answering the question of how the four sources of international law do work as primary rules by meeting Hart’s three characteristics of obligation. The legitimacy of these primary rules is further evidenced by the existence of secondary rules that validate them.

Article 38(1) of the ICJ Statute

Article 38(1) stipulates the four sources of international law as follows:

- ‘International conventions, whether general or particular, establishing rules expressly recognised by the contesting states;

- international custom, as evidence of a general practice accepted as law;

- the general principles of law recognised by civilised nations, and

- subject to the provisions of Article 59*, judicial decisions, and the teachings of the most highly qualified publicists [legal experts and scholars] of the various nations, as subsidiary means for the determination of rules of law.’

*Article 59 establishes that ‘the decision of the Court has no binding force except between the parties and in respect of that particular case.’

International Conventions

International conventions, also known as treaties, act as a primary rule that generates obligations upon states. One example is the 1961 Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations (VCDR), which codifies rules on ‘diplomatic intercourse, privileges, and immunities [that] would contribute to the development of friendly relations among nations.’ The VCDR meets Hart’s first characteristic of obligation as there is an insistent demand for conformity and social pressure due to the practice of diplomatic reciprocity. For example, states feel pressure to conform to the VCDR to ensure their diplomats have freedom of movement in the receiving state, and are not subject to arbitrary arrest, or a lack of secure conditions, as indicated in Article 27(5). Second, as the sole and official standardised framework that governs diplomatic relations, the VCDR acts as a necessary condition for the conduct of successful and friendly diplomatic relations among contesting states, which in turn plays a fundamental role in the sending and receiving of states’ foreign policy agendas, as well as in international relations. Third, the VCDR often requires actions that may compromise the agency of the state. For example, Article 31 highlights that the receiving state must grant diplomatic immunity to a diplomat who may have committed a crime in their territory. This instance highlights a compromise since the receiving state may not wish to do this because the crime might fall under its jurisdiction, but it is pressured to do so.

International Custom

Similarly, international custom also acts as a primary rule that generates obligations upon states. One example is the prohibition of torture, which has been referred to as an international custom based on the peremptory norms of general international law (jus cogens) cases such as the Prosecutor v Furundžija, in which the latter was convicted of co-perpetrating torture against a Muslim woman in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The prohibition of torture meets Hart’s first characteristic of obligation as there is an insistent demand for conformity and social pressure due to torture being classified as an elite peremptory norm that states prioritise and respect, from which no derogation is allowed. Second, the prohibition of torture acts as an essential rule for individuals to live a life that embodies human dignity without constrains, disruption, or harm. Third, the prohibition of torture requires actors to behave in a way that may go against their desires. For example, a state may wish to employ psychological and physical torture for political and personal gains, but refrains from doing so because of international custom, benefitting those who would have otherwise been tortured.

General Principles of Law Recognised by Civilised Nations

In addition to international conventions and international custom, general principles of law recognised by civilised nations also act as a primary rule that generates obligations upon states. It is important to highlight that while they are defined as ‘norms of general or universal application’ to complement international law gaps, they are formed in domestic courts according to legal scholars and the third report on general principles of law by the Special Rapporteur of the International Law Commission (ILC). One example that shows how the general principles of law meet Hart’s three characteristics is the principle of estoppel, which is when a ‘state party to an international litigation is bound by its previous acts or attitude when they are in contradiction with its claims in the litigation.’ This was brought up by Argentina against Chile in the Argentina-Chile Frontier case with the Court of Arbitration. First, there is an insistent demand for conformity and social pressure as estoppel is classified as a principle that embodies good faith, honesty, and fairness. Deviating from the principle of estoppel would signal to other countries that the state in question does not hold these three values in high regard. Second, the principle of estoppel acts as a necessary rule for states to keep parties accountable for all their actions. It also attempts to prevent misinterpretation of facts. Both are vital for maintaining social life. Third, the principle of estoppel may require actors, depending on their circumstances, to keep consistent acts and attitudes during litigation, rather than developing a new opinion that negatively impacts the opposing party.

Judicial Decisions and Teachings of the Most Highly Qualified Publicists

Lastly, judicial decisions and the teachings of the most highly qualified publicists of the various nations also act as a primary rule that generates obligations upon states. Article 59 of the ICJ’s Statute sets out that the judgments and teachings of influential publicists are only binding to the parties involved in a particular case, and that decisions are independent, and do not create a precedent for future cases. Since the source is self-explanatory, examples would entail the judgments of the ICJ and the opinions of recognised lawyers and academics that work alongside the ICJ and the ILC to bring clarity to cases in international law. Moreover, ICJ judgments and ILC opinions meet Hart’s first characteristic of obligation, as there is an insistent demand for conformity and social pressure on states to safeguard their legitimacy. More specifically, this demand is based on the expected respect shown towards the ICJ, as the principal judicial organ of the UN, as well recognised academics. Second, the ICJ judgments and ILC opinions act as necessary for the pursuit of justice internationally and the reconciliation between states. Third, the ICJ judgments and ILC opinions will often require actions that may compromise the agency of different states. These compromises depend on the ruling itself, but highlight instances where a state may have to give up territory, re-draw delimitation marks, or stop committing actions that may be harming civilians.

In decoding the language of law, we not only come to learn that international law is considered law by embodying the essential elements of Hart’s Concept of Law, with an observable union of both primary and secondary rules, but also to recognise that acknowledging its legitimacy as a legal system, rather than succumbing to pessimism, is the first step towards the pursuit of international justice.

This article was originally published in OPR’s Issue 13: Language.

Danilo Angulo-Molina holds an MSc in Global Governance and Diplomacy from Trinity College, Oxford. He is a Senior Editor at the Oxford Political Review.