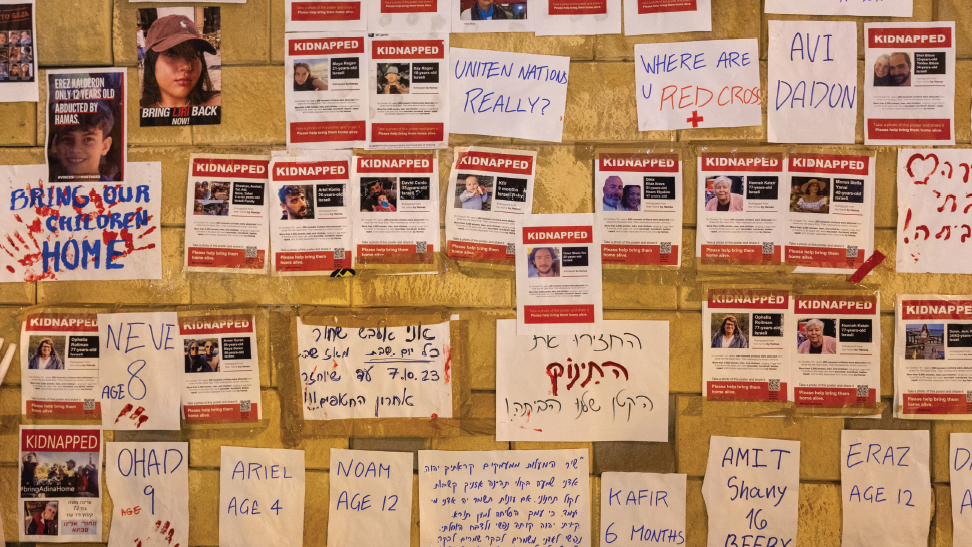

My cousin, Ofelia Roitman Feler, was held hostage in Gaza for fifty-three days. On several occasions, I’ve walked down a street in my San Francisco neighborhood only to see Ofelia’s face staring back at me, her poster one of hundreds covering the wall of a local building. These posters are one way among many that Israel’s advocates issue calls to #BringThemHome. They use the figure of the hostage as a seemingly apolitical way to illustrate Hamas’s cruelty and Israel’s victimhood. The figure of the hostage, though, is anything but apolitical. Rather, hostages like Ofelia are coopted to justify continued violence, expulsion, and exploitation. The figure of the hostage, therefore, needs to be complicated.

Americans’ discursive use of the hostage emerges from a long political tradition. For French philosopher Emmanuel Levinas, the figure of the hostage represents the prototypical ethical subject. Levinas is known for putting forth a vision of ‘ethics as first philosophy,’ wherein our responsibilities to others are always primary. Ethics, for Levinas, supersedes politics. From the instant we encounter the other face to face, before we have any chance to think or choose, we are held hostage by our ethical responsibility to the other. In this way, Levinas turns to the figure of the hostage to emphasise how deep our responsibility to others runs: we are captivated by and beholden to others in the way a hostage is held captive by her captor, unable to escape our ethical responsibilities to others even if we tried.

In an interview titled What No One Else Can Do in My Place, Levinas calls this ethical hostage ‘someone who is called to give.’ He goes so far as to claim that becoming an ethical subject means we must each think of ourselves as a potential Messiah: ‘I am here to save the world,’ and ‘I’ am the only one who can, we each must think.

These ethics are highly political. They rest on the assumption that the world – or the other – always needs saving, and that each of us has an individual duty to save it. But Levinas never stops to consider that others might not want what we are ‘called to give,’ or that they might rebuff the salvation we offer. Israel never stops to consider this possibility either: in the early years of Zionist settlement in Palestine, David Ben-Gurion was reportedly ‘truly stunned’ that Palestinians refused the benefits he thought Zionist ‘modernity’ would bring them. Their refusal didn’t matter – Zionist modernity was forcibly ‘given’ to them anyway.

Like Levinas’s hostage, the Israeli state is infused with the qualities of both passive victim and indispensable savior, qualities that peremptorily justify anything the state might do. Israel, Levinas wrote in 1979, is ‘the most fragile, the most vulnerable thing in the world,’ because it is filled with historically victimized Jewish citizens, and surrounded by hostile neighbors. And yet, on the very same page, Levinas says Israel possesses the ‘very real strength’ needed to ‘elaborate… a political doctrine’ from which all the world will benefit. ‘[T]he salvation of all others’ depends on Israel’s unique ability to construct a universal politics worthy of its ethics.

In practice, this logic serves to justify rampant violence and dispossession from the start. It lays the groundwork for Israeli historian Benny Morris to argue, for example, that ‘Jewish suffering and desperation’ justified Zionist aims of ‘dispossessing and supplanting the Arabs.’ Dispossessed Palestinians, for their part, are criticised for being ‘unwilling or unable to understand… the Zionist claim to the land.’ Had they relinquished themselves to Zionism, Morris says, Palestinians would have grasped ‘the movement’s strength, to their own benefit’ (emphasis added). In other words, Palestinians are at fault for refusing to be ‘saved.’

In this way, Zionism’s politics, like Levinas’s ethics, inscribes an intractable ‘asymmetry’ between Israelis and Palestinians: Palestinians’ right to presence is made contingent upon their embrace of anything Israel does or offers, but Israeli presence in Palestine – like the hostage’s presence for the other – appears non-elective, and therefore innocent and inherently justified. Indeed, in reference to the ethical subject, Levinas proclaims that ‘we do not choose’ the responsibility we bear; about Zionist militarism in Palestine, he likewise exclaims, ‘En bererah, “no choice!”’

These dynamics carry forth in the present war. Today’s defenders of Israel have described the IDF’s mission in Gaza as liberatory: upon their invasion of Gaza, soldiers hung rainbow flags on their guns with ‘In the Name of Love’ written on them. Israel simply wants to ‘free Palestine from Hamas,’ advocates explained. Like a Levinasian ethical subject, the IDF soldier is positioned as an apolitical savior working toward universally just ends. The violence he perpetrates is thus paradoxically described as for the benefit of his victims, rather than merely against them. According to this logic, Israeli presence in Gaza is made preemptively innocent and warranted, no matter the destruction it brings.

The politics inscribed by Levinasian ethics are in no way unique to Israel’s treatment of Palestine. In his book After Evil, Robert Meister points out that Levinasian thought undergirded much of early twenty-first-century international politics: ‘the first imperative of Levinasian ethics is to avoid historical contextualisation,’ so that only ‘saviors’ have an automatic right to presence and right to rule. In recent decades, Meister points out, this logic has justified various and neo-colonial ‘wars of rescue.’ ‘[E]ven when it invades and occupies,’ Meister says, ‘it does so for ethical, and not political, reasons.’ Invasions and attacks, therefore, appear just.

This should beg the question of whether the world really needs saving, as Levinas suggests, or if the saviors are what we now need protection from. It is upon these grounds that Levinas’s friend and contemporary, literary theorist Jacques Derrida, sought to complicate Levinas’s thought. By shifting from Levinas’s term ‘hostage’ to his own ‘hôte,’ Derrida subtly diverts the emphasis of Levinas’s concept. The word “hôte” means both host and guest. The hôte, in other words, is he who is ‘called to give’ to others, as with Levinas, but he is also one who receives from others – specifically, he is one who needs to receive forgiveness. Derrida writes:

‘There would be, there sometimes is… an injunction to ask for forgiveness, to ask the dead or one knows not who, for the simple fact of being there [etrela], alive, that is to say, for surviving, for being here, still here, always here… a being there originarily guilty. Being-there: this would be asking for forgiveness; this would be to be inscribed in a scene of forgiveness, and of impossible forgiveness.’

The hôte, in other words, whether guest or host, both gives and receives, because even in giving all he has to the other, he is still guilty and must beg the other for forgiveness. Forgiveness, though, proves to be ‘impossible’:

‘when someone forgives someone else… well, then, one must above all not tell the latter… one must not say, that one forgives… not to recall or to manifest that something was given (forgiven, given as forgiveness), something was given back again, that deserves some gratitude or risks obligating the one who is forgiven… [This] opens a scene of acknowledgement, a transaction of gratitude, a commerce of thanking that destroys the gift… One must therefore say nothing.’

Flipping Levinas’s story on its head, Derrida suggests that true giving – true for-giving – should not be done. One cannot give without expecting to receive in return, thus cancelling out the gift of forgiveness. Derrida therefore leaves us with the notion that the subject is both ‘originarily guilty,’ and that this guilt cannot be truly remediated. One’s presence, indeed, one’s very existence, cannot be summarily justified or made innocent.

What Derrida calls ‘hospitality’ thus ‘undoes’ that which appears to be justified, innocent, and certain. ‘Hospitality,’ Derrida goes on to say, ‘is the deconstruction of the at-home.’ Applied to the scene of Israel and Gaza, Derridian hospitality – filled with hôtes rather than hostages – would shatter any quality of innocence in Israeli presence. It would lead even the actual hostage to beg forgiveness for ‘being-there,’ a forgiveness they will never really receive.

Derrida’s subtle yet profound critique of Levinas thus brings us toward a radically different politics, one that inscribes constant self-questioning in place of self-certainty. Levinas’s ethics, as we have seen, work to legitimize the settler policies Benny Morris defended above. Even while ‘dispossessing and supplanting the Arabs,’ Morris claims, it was best for Zionist settlers ‘not to dwell’ on the ‘moral dubiousness’ of what they were doing, ‘lest it generate an infirmity of purpose’ in the unquestionably just Zionist cause. It is precisely the ‘unquestionable’ nature of the cause that Derrida forces us to unravel.

Whereas Levinas’s hostage inscribes the automatic right to Israeli presence, Derrida effectively complicates that position. The Derridian Israelis’ presence cannot be made ethical, and is never forgiven, even if the Israeli did not choose to be where she is – even if, like Ofelia, she was taken hostage. While Levinas’s ethics lead to neo-colonial wars of rescue, Derrida’s nudges in a different direction – toward perpetual self-questioning, one’s presence never (for)given.

I experienced overwhelming gratitude and relief the moment Ofelia was returned from captivity and rejoined her husband, children, and grandchildren. I wish nothing but the same for the remaining Israeli citizens held captive. Even so, it is overwhelmingly clear that discursive focus on Israeli hostages, especially in the United States, works to excuse and promote relentless and brutal Israeli attacks – and to quash dissent – instead of doing anything to reunite captives with their families. Were calls to ‘Bring Them Home’ to be followed by demands for a ceasefire – the only established way to free captives – things would be different; instead, these calls accompany and provide cover for merciless aggression, aggression that has killed more hostages than it has rescued. A fundamental reframing is therefore needed.

Unlike a hostage, the Israeli state – unequivocally backed by the world-superpower and in possession of more military aid than any other nation on Earth – bears the overwhelming power to decide. Levinas’s dictum that Israeli militarism carries ‘En bererah, “no choice!”’ could not be farther from the truth. The indiscriminate murder of 35,000 and total annihilation of Gaza is not a passive act, nor can it be made to appear as such.

Rather than clinging to the innocent or victimary subjectivity of the hostage, Israel and its supporters are therefore implored to take a page out of Derrida’s book and ‘undo’ the all-too comfortable sense of being unquestionably ‘at-home,’ and ‘dwell’ on the ‘moral dubiousness’ of what has been done. Only then might they realise that the state will never be forgiven for the crimes it now perpetrates.

This article was originally published in OPR’s Issue 13: Language.

Daniela Tolchinsky is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Political Science at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. She is currently a visiting scholar in the History of Consciousness program at University of California, Santa Cruz.