From a certain angle, Singapore really does look like paradise. The East Asian city-state is at or near the top of virtually every international ranking of merit: it has the second-highest GDP per capita, the world’s best schools, and the seventh-highest life expectancy, and it ranks in the bottom ten for crime and corruption. Homelessness is basically non-existent, unlike in similarly rich and densely populated places like Hong Kong; the country has only around 500 homeless people, and housing is broadly affordable—three-bedroom flats can cost as little as US$217,000, or around four years’ wages.

What makes this all the more extraordinary is just how different things were when Singapore gained independence fifty-eight years ago. In 1965, GDP per capita was only $516—less than the world average and below countries like Mexico, South Africa, and Venezuela. Unemployment was at double digits, and almost 70% of Singaporeans lived in kampongs, or rural wooden shacks, which were often without running water and shared with farm animals. Moreover, the country had virtually no natural resources or developed industry.

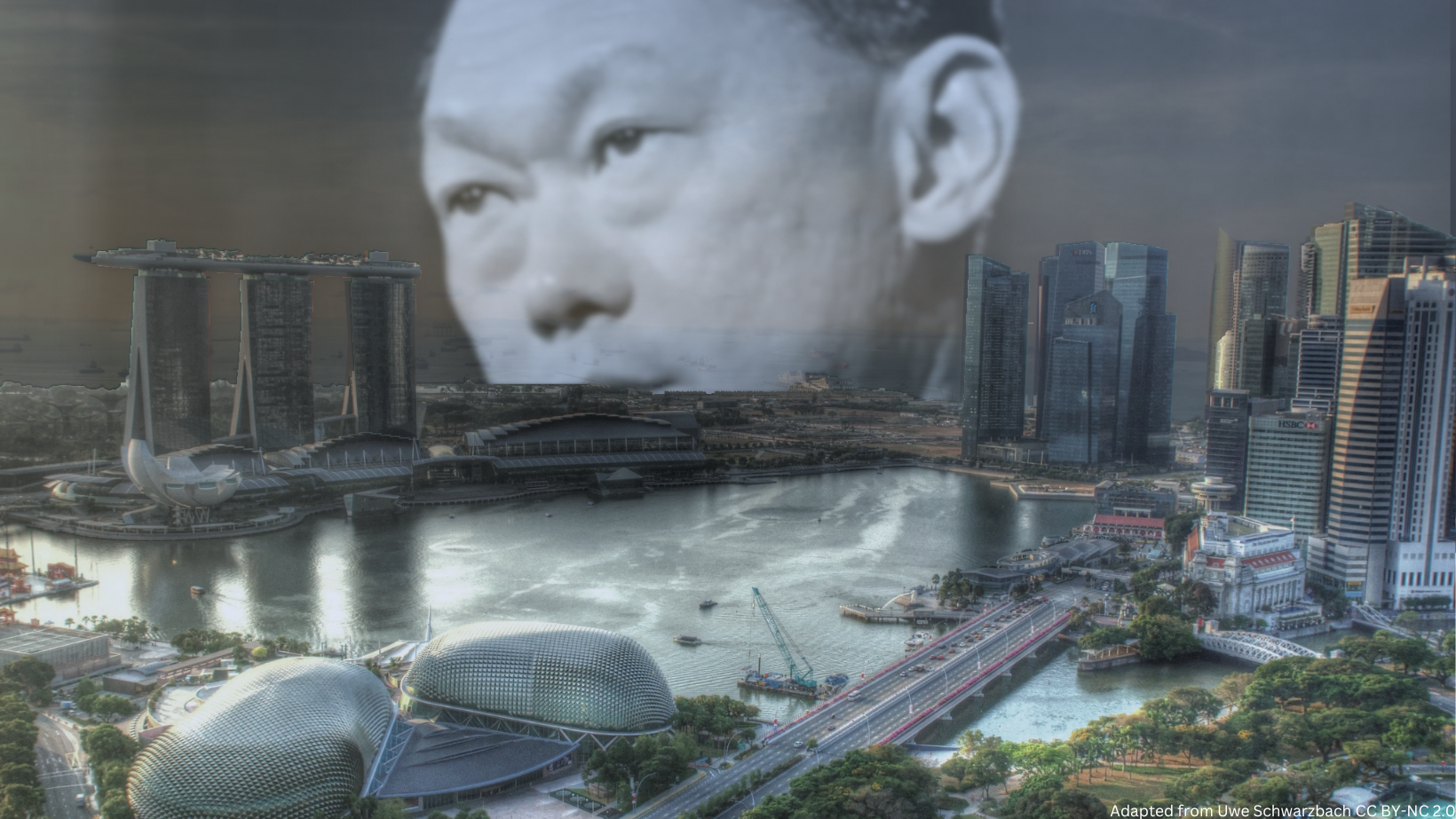

Just as improbable as Singapore’s future economic success, however, was its very survival: independence had been thrust upon it when conflict between the Malay and Chinese populations led to the island’s expulsion from Malaysia. As a result, Singapore’s only land border was with a hostile, far more powerful nation, and the country’s population was deeply divided. Race riots just a year earlier resulted in nearly 500 casualties. It should come as no surprise, then, that in 1957 Lee Kuan Yew—who would go on to transform the city-state as its first premier—described independence as a ‘political, economic and geographical absurdity.’

And yet, within the span of a single generation Singapore went, as Lee titled his memoir, From Third World to First. The development-at-all-costs focus of Singapore’s early leaders means that the kampongs are but memories for the millions of Singaporeans who now gaze out the windows of fancy condominiums at a skyline dominated by skyscrapers. Little wonder, then, that panjandrums of all stripes—from dictators Kim Jong-Un and Xi Jinping to former British Chancellor Richard Hammond and MP Wes Streeting have extolled the virtues of the so-called ‘Singapore Model.’

Yes, Singapore might look like paradise. But it is not. If there is anything the Singapore Model can teach us, it is not the sanctity of free markets or even the virtues of government intervention, as many have incorrectly claimed. It is that development is often a zero-sum game, with rapid progress in one area leading to rapid backsliding in others. The transformation of Singapore from developing to developed demanded social engineering on an unfathomable scale—a trade-off the government gives its people no choice but to accept.

The most obvious sacrifice Singapore has made is liberal democracy. But it is unfair, as many do, to call the city-state a dictatorship. According to the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index, Singapore is a flawed democracy—putting it in the same bracket as the United States (albeit with a much lower score). In Singapore, elections are held regularly, citizens are free to vote for opposition parties, and there is no ballot-box stuffing.

Singapore may not be a dictatorship, but neither is it particularly democratic. The People’s Action Party (PAP), which has ruled since independence, does not rig elections because it knows there is no need to. When in 2020 the PAP won 83 of the 93 seats in the national legislature with more than 60% of the popular vote, the party viewed the results as a major failure because its dominance is so total. The government runs a blatantly unfair system of patronage, making voting against it an unsavoury prospect. In 2006, for instance, former Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong promised to spend $63 million on development in Singapore’s Hougang area if they voted PAP. But if they voted for the opposition, he warned, it would become a ‘slum.’ Moreover, the PAP retains total control over the drawing of electoral districts, resulting in a severely gerrymandered map with multimember constituencies that inevitably benefit the ruling party.

Freedom of speech, too, is severely curtailed. While foreign newspapers and anti-government media outlets are allowed, the government’s Protection From Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act gives it the power to remove or ‘correct’ any news article it wishes. Criticizing the government will not see you ‘disappeared’ in the middle of the night by the secret police, but you might face defamation suits brought by a horde of government lawyers, which is among the PAP’s favourite means of suppressing dissent. The government has sued everyone from opposition politicians to foreign magazines—even for millions of dollars—and has never lost a case.

The right to protest is even more restricted—to legally organize a demonstration requires a police permit. Otherwise, the gathering is unlawful and often dealt with harshly. This happened in famous cases such as that of Jolovan Wham, who was arrested for holding up a sign with a smiley face on it.

Fundamentally, the Singaporean government does not see elections as a choice between the PAP or the opposition, but between loyalty and insubordination. The PAP gave Singaporeans wealth, safety and prosperity. Surely, electoral support is the least they could give in return. According to this line of argument, opposition voters are, as Premier Lee Hsien-Loong described them, ‘free riders’ in Singaporean society. Electing the PAP, as he put it, is the ‘duty’ of all good citizens. The farcical aspects of Singaporean democracy were demonstrated even more clearly in a 2006 speech by the then–prime minister, in which he famously stated that the opposition’s job was simply to ‘make life miserable for me so that I screw up,’ and that if they got too powerful, he would have to ‘fix’ them.

For many authoritarian leaders, the acquiescence of their people is the end goal of their interventions. But Singaporean leaders have far more extensive aims. Perhaps the most infamous example of their paternalistic intrusions into Singaporeans’ lives is the ban on the sale of chewing gum, which was instituted in 1992 as part of a crackdown on littering. Far more absurd, however, was the government’s ‘Operation Snip Snip’ in the sixties. Men with long hair were subject to a laundry list of punishments—they were the last to be served at government offices, they were fired from government jobs in some cases, and, if they were foreigners, were denied entry into Singapore. All of this, Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew explained, was necessary because ‘we did not want the young to adopt the hippie look.’

Indeed, Lee never shied away from admitting to his government’s intrusions into people’s personal lives. As he said in a 1987 speech: ‘I am often accused of interfering in the private lives of citizens. … And I say without the slightest remorse, that we wouldn’t be here, we would not have made economic progress, if we had not intervened on very personal matters —who your neighbour is, how you live, the noise you make, how you spit, or what language you use. We decide what is right.’ In other words, ‘If this is a “nanny state,” I am proud to have fostered one.’ Wherever personal freedom stood in the way of Singapore’s sprint to paradise, it had to give way.

This conviction carries into the government’s management of relations between Singapore’s three main ethnic groups: Chinese, Malays, and Indians. No intervention has been deemed too extreme in the pursuit of ‘racial harmony.’ For example, public housing (in which most Singaporeans reside) is subject to a strict system of ratios in order to prevent the formation ethnic enclaves. To limit linguistic divisions between these groups, English was adopted as the country’s lingua franca. As such, most Singaporeans’ mother tongues are taught only as second languages.

But one group has always been neglected in this paternalistic quest for equality. Immigrants—who made up 2.5 of the city-state’s 5.7 million people in 2020—almost never enjoy the same quality of life as Singaporeans unless they are highly skilled Western expats. As Human Rights Watch documented, work permits for most low-skill immigrants are tied to their employer, leaving them vulnerable to exploitation. Legal protections are few and far between: These immigrants are exempted from laws limiting labour hours, and are often transported in the backs of lorries, packed together like sardines, leading to thousands of injuries and even deaths in the last decade. Living conditions are often horrid, with as many as twenty people to a room, all sharing a single bathroom. It’s no wonder that immigrants made up almost 90% of all Singapore’s COVID cases.

Fundamentally, studying Singapore reveals that there is an enormous tension between utopia and freedom. Give the people freedom, and they might decide they no longer want to live in a Utopia—they might decide they want to litter, consume drugs, or do the bare minimum at work. In Singapore, by contrast, the people are, for the most part, only free to choose when their choices will not interfere with the ongoing project of national perfection.

From the perspective of a country like Britain—where the government exists in a perpetual state of chaos, and the healthcare waiting list exceeds Singapore’s entire population—it might be tempting to conclude that Singapore made the right call when it sacrificed freedom, liberalism, and accountability in pursuit of utopia. Singapore’s leaders are particularly fond of pointing to other nations (often India) which started from a similar level of development but pursued democracy instead, a choice for which they paid the price.

But there is increasing evidence that Singapore’s authoritarian bargain is coming under strain. A government can only function effectively without public accountability and a free press if it is squeaky clean; yet recent scandals, which have seen resignations and arrests for various corrupt dealings, including bribery and severe conflicts of interest, have shaken the PAP to its core. The success of Singapore’s authoritarian social engineering should not blind us to the fact that virtually everywhere else such policies have been tried—from Uganda’s ujamaa villages to China’s zero-COVID policy—they have ended in disaster.

This article was originally published in OPR’s Issue 12: Utopia.

Martin Conmy is a second-year History and Politics student at The Queen’s College, Oxford.