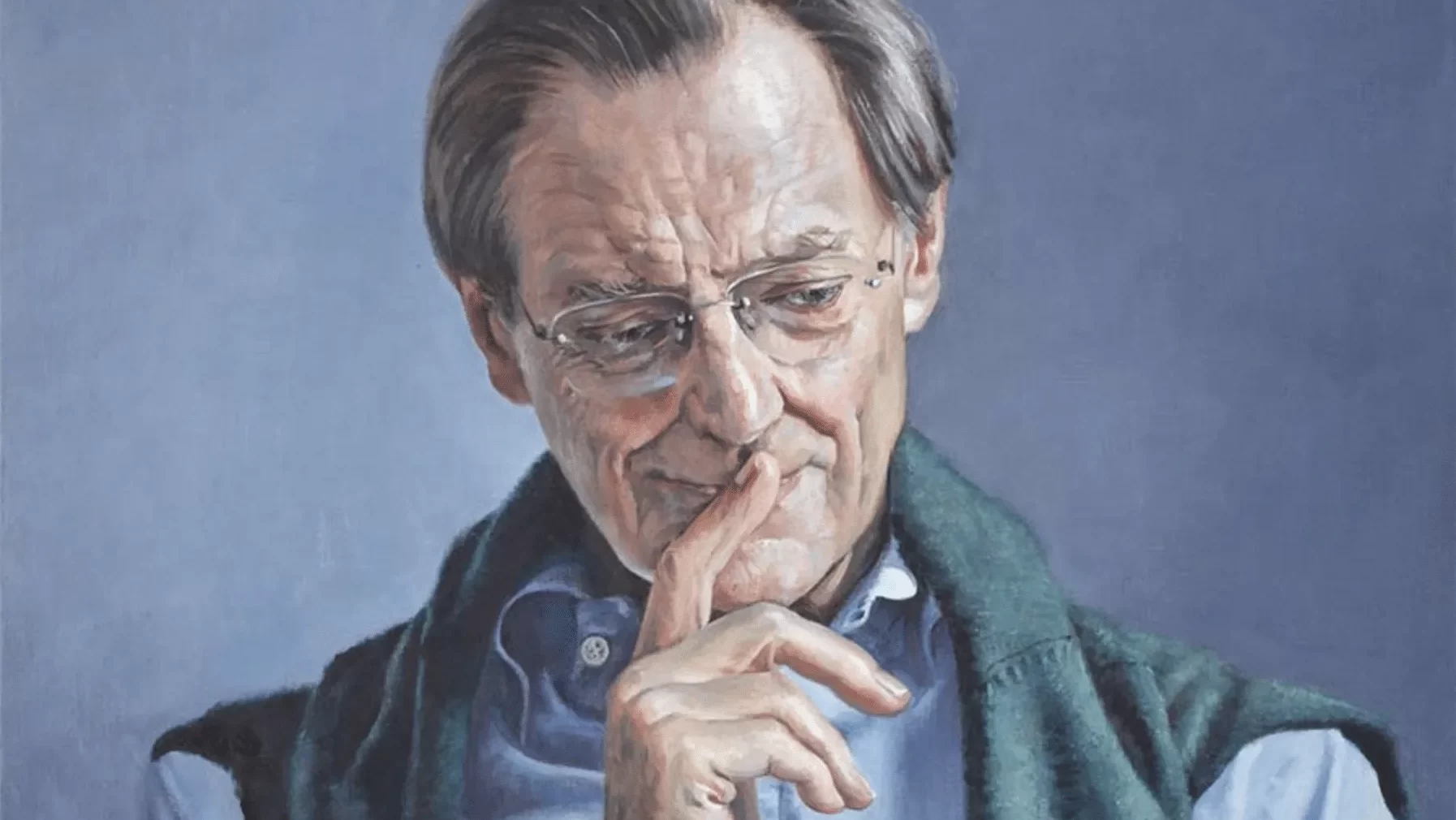

Today we are joined by Professor Quentin Skinner. He is an intellectual historian and currently the Barbara Beaumont Professor of the Humanities, and Co-director of the Centre for the Study of the History of Political Thought at Queen Mary, University of London. Professor Skinner has won numerous prizes for his work, and between 1996 and 2008 he was Regius Professor of History at the University of Cambridge.

Since the 1980s, Professor Skinner is also the general editor of the Cambridge Texts in the History of Political Thought series. So, I want to start this discussion by asking you: how did this series begin?

Well, first, thank you particularly for asking about the Cambridge Texts series because this has been one of my most long-standing projects. I mean, like most people, I’ve given an awful lot of interviews in my time, and no one’s ever asked me about this. And so, I’d really like to go into it.

How did the series begin? Well, the starting point was some conversations I had with Richard Tuck when I returned to teaching in Cambridge, in 1979, after a five-year absence — I was away for those years in Princeton. Now, Richard Tuck was at that time my closest colleague in the teaching of the history of political theory at Cambridge, and Richard told me — not exactly that he was having difficulty in his teaching; he was a wonderful teacher — but there was a problem in our subject if we were going to try to treat it in a genuinely historical way, because there were simply no editions of the less well known political texts. The upshot of that discussion I had with Richard was that we decided to talk to the Cambridge University Press about the possibility of setting up a series to remedy this specific lack.

Now, I had by then been working for quite some time with Dr. Jeremy Mynott. Jeremy was, at that time, a rising star amongst the commissioning editors at the Cambridge Press, and he had already been the editor — and I must say, an absolutely brilliant editor — of my book, The Foundations of Modern Political Thought, which Cambridge had published in 1978. So, I worked with him for some years on that book, and I knew him well. So, I contacted Jeremy and, as I recall, he then arranged a meeting with Richard and me and himself at the Press. And in the course of that meeting, it became very clear that he had thought very carefully about Richard Tuck’s ideas. Jeremy liked the idea of a series committed to expanding the range of texts that students were invited to study, and he asked us to provide a list of the texts that we had in mind. But he was also very keen at that point — and indeed, at all points — to give the series that we now had in mind a much stronger profile — and also an economically stronger profile — by including new editions of the major, the most canonical texts that would be included in our new series. And so, he also asked us to consider what canonical texts we should make sure we were also doing new editions of for the series. So, there’s how it started.

How did both you and Raymond Geuss come to be co-editors for the series?

That arose when Richard Tuck and I started to think about specific texts. It became clear to us that we needed a third editor. Now, this third editor, we really had in mind for 19th and 20th century texts, because Richard and I were both early modernists. But we also have in mind someone who, alternatively, might know a lot about classic texts and texts in the ancient world. Now, Richard, of course, himself knows a great deal about classical political philosophy. But we immediately thought of Raymond Geuss as our ideal third editor because he was someone who’s equally at home in classical texts — I mean, his Greek and his Latin are top notch, and he’s extraordinary well read in classical political philosophy — but at the same time, of course, he is an expert on 19th and 20th century philosophy, especially German philosophy and anything from Hegel to Habermas. So, Raymond seemed the obvious choice. Now he particularly seemed an obvious choice to me, because when I was at Princeton for those five years, he was also there. And I got to know him extremely well; we spent much time together. It was a great education for me, and I could see that he was someone with whom it would be very easy to work. Finally, and of course, crucially, Raymond had just left the United States, and he had come to teach in Cambridge, where he spent the whole of the rest of his career. And in 1981, he published his book on Critical Theory with the Press. So, the Press already knew him, and Jeremy Mynott already knew him. And so that was how Raymond got added. But I do want to say that, since the texts were mostly edited by Raymond and me, nevertheless, the original thinking came from Richard Tuck.

I’m interested in what your initial aims really were more substantively for the series.

The initial aims — these were hammered out in, what I recall, a very enjoyable day that Richard Tuck and Raymond Geuss and I spent at the Cambridge Press with Jeremy Mynott, where we went through the Western canon, and made a list of the texts we would most like to see included. And I should say that we all agreed in those days that we would concentrate on the Western canon. I mean, we are talking about 50 years ago. And in those days, it was that range of texts, which was almost exclusively being taught in universities, and certainly very widely taught, which of course, a publisher has to have their eye on in relation to the question of whether this is an economically viable idea.

Now, the initial aim, since you put it in that way, from Jeremy Mynott’s, point of view, was that he thought we could have arranged an eventual list of 30 volumes, which was a very large commitment from the Press. And he envisaged those 30 volumes as coming out in batches. And they were going to be batches of six texts. And speaking still of initial aims, he also noted down — and this became a cardinal principle of the Cambridge Texts series — which is that we would never produce extracts from texts; we would either publish the complete text, or we would not publish. That became a very big headache in one or two cases. I mean, for example, much later with Montesquieu, De l’Esprit des Lois, where we were publishing an enormous book and in translation. And we never did produce snippets, which was the usual way of doing it. But of course, that already tells you how to interpret the text, because it’s only giving you a little bit. So, the cardinal principle, as I say, was only complete texts. And the final initial aim that Jeremy had for the series was that it would be good if the editors themselves contributed editions to the series. Those were our initial aims.

From my point of view at least, I think most of those aims had been achieved. Would you say so yourself?

I think I can say that they were not only eventually achieved, but they were very greatly surpassed. I mean, we were conservative at first, and the first batch of six were mostly really major texts, it has to be said: Aristotle, Bentham, Machiavelli, Locke. Those ones I immediately remember. There was the other two; [Leibniz] was one, yes. And the sixth one was Constant. That first batch of six texts was published all together in 1988. And it already included a text produced by one of the editors, because I was the co-editor with Russell Price of our Machiavelli text, The Prince. And indeed, in our next batch, which came out in 1991, Richard Tuck’s edition of Leviathan was included in the batch and went on to be one of our big best sellers. And there was a second editor of the series who had contributed a text to it.

What I think I should be stressing really here is that by then, by the early 90s, we started to make good on our promise to include many lesser texts. And we had some, by the standards of those days, obscure texts in our early list, including Baxter’s Holy Commonwealth; I remember Botero, The Reason of State; Christine de Pizan, the first of a number of feminist writers who we were very keen to include; Loyseau’s A Treatise on Orders; de Vitoria, on early modern colonization — which, of course, had to be translated from Latin — a very good edition done for us by Anthony Pagden. So, by the early 90s, we got a number of colleagues at Cambridge helping us with much more obscure texts.

But then, the 1990s saw a big change in the series. And when I speak gloriously of how I think we surpass the original aims, I’m thinking of these changes. Well, one was that Richard left for Harvard. And so, he resigned as an editor. And thereafter the series was edited by Raymond Geuss and me. It was only at that point that Raymond and I took over. Another change was that Jeremy Mynott was promoted in the Press, and indeed eventually became chief executive of the whole University Press. And as editor of our series, he was replaced by the young Richard Fischer, who also had a sensational career in the Press and ended up as managing director. Now, Richard decided to turn this series into something much larger. And so, Jeremy’s original target of 30 texts was not only surpassed easily in the 1990s, but — by the time Richard eventually felt that we’ve done enough, when you close the series for commissioning, that would have been sometime around 2005, I think — by then we have published not 30 texts, but nearly 130 texts.

What are some challenges that have been encountered in such a big project?

Well, that’s a good question. I mean, there were many challenges as the series grew so fast. I mean, I don’t want to sound self-pitying, but one of the challenges was faced by Raymond Geuss and me because we were pretty busy and we signed on for 30 volumes, but we edited, as I said, nearly 130 volumes. But the business of seeing each one of those through the Press was very large. We had to read all the drafts of all the introductory materials. Sometimes those were brilliant and could be passed straight away. Sometimes they needed a great deal of work. Sometimes we would even had to have them refereed. But basically, we served as the two referees for everything it was possible, as well as reading everything that was published. So, one challenge was simply the amount of work it turned out we had agreed to put into this project.

But another challenge we encountered — which I think it was a little bit innocent of us not to have realised that this was going to be a problem — was that our original idea was that these texts should run from antiquity to the present day. But we encountered a very large challenge, in fact, an insurmountable challenge, when we tried to include 20th-century texts. We managed one or two, which were special cases: for example, Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks, which Richard Bellamy edited for us. But in general, what we found [for] major texts from the 20th century or even more minor ones was that no publisher was going to give us any copyrights. Of course not. And I can remember when we tried at one point to include something by Collingwood in the series, and I wrote to the Oxford Press saying: “would you guys let us have the copyright to this text of Collingwood’s?” And they wrote very courteously, but saying: “well, it’s never been out of print. And we print it all the time. So why would we give it to a rival to reprint as well?” It’s a very fair question. And the answer was, of course, there’s no reason at all why publishers should do that, and every reason not to do that. And so, one of the challenges that we never managed to overcome was that we just could not get texts that have been published in the 20th century. The only exceptions would be if they were out of copyright, but of course those were the days in which copyright was suddenly extended very much greater length of time: 70 years. And so of course, that effectively wiped out the 20th century.

The main challenge that we faced — except of course it was the usual one with academics — was that one or two, or three or four or several of the people who were approached to act as editors agreed, signed the contract, and then never managed to produce. This does happen with academics. And it left some gaping gulfs. And one which I particularly regret is that, although we published Machiavelli’s Prince, we have yet to publish Machiavelli’s Discourses in the series — it is probably in some ways the more important text, the Discourses. And the problem there was that we gave the work to be done by Russell Price again, who had done a wonderful job on The Prince — and he set to work, but he fell ill, and not much got done. And then very sadly, he died, with very little of that work achieved. And we then tried to recommission it. And the person we commissioned couldn’t manage to do it. And we then had to recommission it again. And that’s only happened quite recently. It’s now in the hands of a really wonderful editor, and I’m sure it will work this time. That’s just one example of something that happened to us a number of times — it’s that people don’t always keep their promises.

Before we finish with the series, I just want to say something about where it stands now because Richard Fischer had closed the series for commissioning around 2005. But Richard retired in 2014, and at that point, I persuaded one of the new stars at the Cambridge Press, Elizabeth Friend-Smith, to reopen the series, and it is now reopened for commissioning. And it has been since 2015. But on a completely new basis. So, this series now exists to publish texts in political theory which are entirely outside the Western canon. That was my idea, after a gap of eight or nine years when nothing happened in the series because it had been closed. And I said to Raymond, you know, we could reopen it, because they will be willing to do it in this way. But Raymond didn’t want to do that. And so I was left as general editor of the series. But of course, we will now be dealing not with the Western tradition, but with the rest of the world. And so, what then had to happen was that a proper editorial board had to be set up, that’s to say, including experts on China and Japan, on Islam, on Latin America, on Africa. So, it’s a different enterprise. Now, I’m the nominal leader, inasmuch as I am the general editor, but all the work now is being done by a very expert series of [editors] on this board, from all over the world. And we have now been commissioning and have started to publish. And several volumes are now out, including volumes on Latin American, and on Japanese political thought. Far more to come, including quite a lot on Islam. And we hope on Africa, too. So, I just want to round off by saying that that’s where we have reached, as I now speak.

Actually, I’ve got one thing I would like to say, which is a final thought about the series. You asked about the evolution of this series. But I’ve also been struck over this long period of my involvement with it, about how the series came to map certain intellectual changes. And one way in which it’s done that stems from the fact that I see all the sales figures for the series, which has sold millions of copies by now if you put the whole thing together. So, what you can do — I’ve even done it — is to track the most popular text of any given year of people who are buying Cambridge Texts in the History of Political Thought. And it’s really interesting. I mean, to start with, the text that sold most copies year, year after year after year, was John Locke, Two Treatises on Government, and then he was demoted. And for some time, the text that sold most was Nietzsche. But in recent years, the text which has been selling most is Machiavelli. So, I don’t know what that tells you about our times or about the teaching of this subject in our times, but that’s just a personal reflection that struck me as we were speaking earlier.

I now want to turn to your own work and career. First of all, did you understand yourself to be doing something that was methodologically distinct relative to your colleagues in the 1990s and the 2000s?

I do not think my approach to the study of intellectual history is distinct at all, if by that you mean that it’s an approach I alone follow. I see my approach essentially as having two main aspects or components, both of which stem from well-established traditions of hermeneutic thought. And so, far from being methodologically distinct, I would like to say a word about the influences that operated on me in my mind; my forebears, people who have said things about something that I have very much agreed with and indeed, learn from. So, first of all, my approach is very obviously indebted to Collingwood, and what he called the logic of question and answer. He and his numerous followers always insisted that the history of philosophy, and perhaps especially of moral and political philosophy, should be written as an account, not of how different answers were produced for a set of canonical questions, but rather as a subject in which the questions as well as the answers are always changing, and in which the questions are set by the specific moral and political issues that seem most salient, most troubling, at different times — and they will continually change and people will continually find that the pressures of their societies are operating in such a way as to raise new questions. So, there’s one source that really mattered to me very much: Collingwood’s wonderful discussion in his autobiography of the logic of question and answer.

But secondly, my approach is even more obviously indebted to Wittgenstein and to his followers in the philosophy of language, and especially J.L. Austin. And what I think of as central to Wittgenstein — you could call his methodology, if you like — is that the concepts of meaning and understanding are not correlative concepts. That’s to say, there is more to understanding an utterance than recovering its meaning. As Wittgenstein always emphasised, ‘words are also deeds’. So, to understand anything that’s been said needs you to attend, not just to the meaning of what someone is saying, but also what they’re doing and saying it — and there is Austin’s famous phrase, ‘how to do things with words’. People are always doing things; speaking is a form of social action. But actually, I think you can go even further than Wittgenstein and Austin here and say that, in political philosophy, the speakers and writers — what they’re going to be doing is, roughly speaking, always aiming either to legitimize or delegitimize some existing state of affairs. And it’s existing states of affairs — the existing political questions and problems — that give them the subject matter on which they then work.

So, I tried to formulate those ideas in a number of essays I wrote in the late 1960s and early 1970s. And my thinking at that time was very much influenced not just by the figures I’ve mentioned, but by my close friend and colleague — who’s been my friend and colleague ever since we were contemporaries at Cambridge as undergraduates together — and that is John Dunn. I owe him so much in these questions of how to think about our subject. But whether John would feel that what I’ve been outlining was something that came to be called, rightly, the Cambridge School, I do not know. But I would rather doubt if he would think that that would be rightly called the Cambridge School. Because, as I say, the kind of contextualisation that John and I were both very interested in — and he wrote brilliantly about in the 1960s — was actually quite a common feature of the intellectual culture of the 1960s. Philosophers of physics, of course, were trying to contextualise what looked like a subject that wasn’t amenable to this kind of historical approach: think of Thomas Kuhn’s work, which — which I think probably influenced both of us — came out in 1962. So, I don’t think it’s helpful to suppose that there’s a Cambridge School. And, of course, our colleagues even protested against that; maybe some of them thought that their own originality would be undermined by anything like that. I’m sure they weren’t as vain as that. But I think that what really happened was that the Cambridge School was a term that got used in the United States by people who were used to Straussianism as a prevailing school. Straussianism was, and is, in the United States the prevailing way of approaching texts in the history of moral and political philosophy. But if that is one school of thought, then there’s certainly another school of thought, which is a contextualising one. And I think somehow that got associated with Cambridge, but it could just as well be associated with the Oxford of Collingwood or Austin, as with the Cambridge of Wittgenstein.

Going back to your methodology, it’s interesting that you mentioned that it’s closely connected to legitimacy. Do you think that the contextualism of the kind that you have elaborated over the years is necessarily realist, or at least connected with what we call political realism? As Annabel Brett has argued, and I quote,

Realism represents a more agent-centred model of politics. Politics is the field of action, and power is pulled into agency, be it of individuals or political institutions or other bodies such as corporations. Skinner was interested in political action, of course; his appeal to the concept of a speech act makes no sense otherwise. But he was also interested in legitimating language as a phenomenon that constrains as much as enables agency within a shared normative horizon. […] Ideology is a kind of political illusion, ‘a set of beliefs, attitudes, preferences that are distorted as a result of the operation of specific relations of power’, distorted (characteristically) in the sense of presenting such beliefs as connected with universal interests when in fact they serve particular interests. Political philosophy can then either critically reveal that distortion, by exposing its relation to power (‘critical realism’), or itself be ideological in the same sense. Political realism stands at one extreme of the interpretative possibilities offered by the basic conceptual architecture of speech acts, and it has a series of consequences for historiography.

[…] Turning from philosophy to history, this in turn supplies an effective historiographical trope, that of exposure — a bringing to light, an unmasking, of the ideological slant of works that may or may not, on the face of it, look ‘political’ in content. The corollary of constructing the ‘outside’ of language in this way is to position the historian, in the present, precisely as an outsider, a critical observer or reporter. The literary form of the exposé is itself a political form, linking the exposé of past and present.

That’s a wonderful passage, which I did not know of; I have not read this piece by Annabel Brett, although I’m an enormous admirer of her work. And I must make sure that I catch up with this article. It seems to me to offer a perfect account of what someone like me is trying to do. As a historian, I’m not prone to ask if my approach is realist myself. But if realism is the appropriate name for the approach that she discussed, then I’m certainly a realist. And I’m struck by how emphatically she’s able to make the point: that what it means here to be a realist is to have a very strong view about agency. And indeed, that ties us back to what we were saying earlier about the project of legitimization and delegitimization, which is what she’s talking about here. That’s to say, no categorical distinction is being drawn by the realist, as she understands this person, between political philosophy and ideology; that in political philosophy, we’ll commonly have — and it would be very surprising if you didn’t — an ideological orientation.

One of the things I tried to do as a young scholar was to take a case where the political philosophy in question — Hobbes’ political philosophy — was the paradigm of the general, systematising, abstract way of thinking about the state. And what I tried to show was that while it was indeed general and abstract and synthetic as an account of the state, it was also a profoundly ideological piece of work. It was counterrevolutionary. It was also an attempt to vindicate the powers that be, by insisting that although you might not have approved of how they have attained power, that was irrelevant to the question of whether you should obey because obedience can be seen not in terms of rights, but in terms of protection. And I tried to show that that whole way of thinking was itself an ideological intervention and the politics — very precisely — of the immediate aftermath of the regicide and the establishment of the English republic. Who is protecting you: Charles? No, he’s dead. Cromwell? Yes, he’s in charge. So, if that’s realism, then I’m a realist.

In recent years, intellectual historians have increasingly used the method of contextualism that you very much pioneered to examine not the distant past, but the more recent past. So, for example, Samuel James has offered a reinterpretation of Pocock’s early work, which led to a dispute among them. Have you ever considered this possibility — of using contextualism to examine the present, and to have disagreements between the historian and the contemporary subject?

An interesting question. Well, as Sam James’s debate with the great John Pocock showed, there are very special problems attendant on writing the history of the present, because you’re going to be writing about people who can answer back. I mean, I never had the problem that, when I explained the precise ideological orientation of Hobbes’ political philosophy, Hobbes will be able to publish an article in which he rubbished what I had said. But this, of course, was what John Pocock sought to do in this particular case. I’m not going to try to adjudicate; I thought that Sam James’s work was wonderful, and very challenging.

But what I want to say, on my own account, is that the approach that I’ve been trying this afternoon to sketch in talking to you purports to be a general hermeneutic. That’s to say, it’s generally applicable — applicable to the present, of course, because it’s generally applicable. So, it’s not just a story about how to get at the past. If you try to use it to get at the present, you encounter all the special problems of trying to get at the present, which I just alluded to. There are special difficulties, of course, attendant on writing contemporary history. And that’s not just because people can answer back; it’s also for a deeper reason, which we’re all familiar with, which is that it’s much more difficult to see our own concepts and our own arrangements as contingent. The goal of the historian, as I’ve been talking about this figure, is to show the contingency of the questions that are raised in the history of philosophy: the extent to which they can be understood if, and only if, you studied the circumstances in and for which they were written. But it’s very much harder, I think, to see your own concepts as having the same kind of contingency. If you see them as wholly contingent, it’s hardly going to be very easy to affirm their truth. So, I think that the history of the present has very great difficulties with attaining the kind of objectivity to which my approach aspires. I think that the historian can at least aspire to give you a sort of objective account — it might not be the account that the agent themselves will give of philosophical works in the past — [but] much more difficult to do it on ourselves.

In a previous interview from 2011, you reflected on your experience of having your own work and ideas made the object of historical contextualism by other contemporary historians. There, you expressed that: “the project of contextualization will never satisfy the person who’s made its object”. But, in light of the turn to the present in intellectual history, do you think that there is nevertheless value in attempting to contextualise the work of a contemporary, even if it may not be completely satisfactory to both the person who is made the subject and the historian?

You’re reminding me of something I seem to have said in an interview about how the subject is never going to accept this. And of course, it was very striking that John Pocock just could not accept what Sam James was telling him and felt that he knew better. And I think that there is always going to be that problem with the contextualising of contemporaries: they think better about what they were really doing. Of course, they may be self-deceiving; they may be forgetting what happened. All sorts of things may intervene for us to want to say that theirs is not the [right] account. But I suppose there’s also — although it’s worrying to see this in what I was saying myself — some vanity on the part of the historian. A feeling that, ‘‘well, that’s not at all how I would have put it myself’; perhaps wanting something more grandiose to be said. So, I mean, my short answer here is — I’m afraid just to begin to repeat what I’ve already said, so I’ll make it short — that of course contextualizing contemporaries can be attempted. And I find it extremely interesting; I enjoy reading biographies of contemporary or relatively contemporary philosophers. But as I just said, some special difficulties attend any attempts to write further.

Recently, Raymond Geuss, your former colleague, has published an intellectual autobiography to explain his present views. Have you considered doing something similar?

My goodness. Well, absolutely not. Although I read Raymond’s book Not Thinking Like a Liberal, and that’s the book that you’re referring to. I read it with real fascination. I think it’s quite remarkable. And he and I had a correspondence about it recently, from which I have learnt a lot, as I always do from interacting with Raymond.

I really think that in this book, he has found a new way of arguing about why some philosophical positions that are presented as universal, as standing outside time, as giving us some kind of general truths, are, in fact, the product of contingent circumstances. So, what I really liked about that book was that I already pretty much agreed with the sort of approach that he used the method of autobiography to arrive at. Because I think that what that book is really saying — and although the target is not very specifically discussed — it’s clear that the sort of target Raymond has is a philosopher like John Rawls, that’s to say, someone who holds liberal principles, and who believes that the theory that he’s generated — which gives us those liberal principles — is itself the product of pure reflection about these principles and their grounding. Now, Raymond believes, in his own case — and this is evident from the account he gives us of his education, a very fascinating account of being educated by these Polish Jesuits, where he was very lucky, you know, they taught him a great deal about European thought, and they also taught him a great deal about mediaeval thought as well — but Raymond also feels that what they taught him was a set of principles which are inherently hostile to liberalism, that these people saw liberalism as a kind of bankrupt form of a capitalist version of an individualist secularisation. So, they thought that everything about it was terrible. But what Raymond is telling us is that he agreed with that — he came to agree with that — but that that [itself] is a contingency, so that, in a way, Raymond was telling us that his hostility to liberalism is socially determined. It was determined by the fact that he was educated by people for whom modern secularised liberalism was anathema. And he doesn’t present himself as someone who is simply inspecting the arguments and deciding against the religion. He presents himself as someone who was conditioned by a particular education. Now, what that leaves us with a very strong sense of, is that probably there’s something very similar to be said about how Rawls came to be the kind of liberal he is — that’s implicit in the book, I think — the whole thing is much more contingent than a philosopher like Rawls would want to think. So, I see this book not just as an attack of liberalism, and thus on people like Rawls; I see it as an attack on the idea that you can have any political philosophy which is an abstract theory where the principles lead in the way that Rawls assumes.

But here, I just want to add, and here I close, that I cannot imagine trying to write an intellectual autobiography myself. It’s a genre of which I am suspicious. I’m suspicious because I certainly think that I would find it impossible to be sure about how I came to hold my present beliefs. I just wouldn’t be happy with any narrative that I could form. It will be too neat; that will be my problem. I’m always tending to put things into pigeonholes and make them too neat. But it will also be likely to be self- deceiving. There will be elements of vanity which I wouldn’t be aware of. There’ll be all sorts of reasons why it’s not a good account. I think it’s very hard for autobiography, at the same time, to be what I’m calling a good account. I think Raymond managed something else, he managed something brilliant and original. But the genre of autobiography, I think, is sort of a kind of guarantee of putting self-deceptions on display.

I really only have one final question for you today. I recently became aware of an upcoming edited volume by you and Professor Richard Bourke, History in the Humanities and Social Sciences. Could you say a bit about it, and what prompted this collection?

I’d be delighted to say something about this book, which I co-edited with Richard Bourke, although he was much the senior partner. And the thinking that went into it was Richard’s rather than mine; it was really perhaps something that emerged out of the very deep investigations that Richard has been engaged in the philosophy of Hegel, which is the importance of historicizing everything and the extent to which the humanities and the social sciences more generally, in our time, have become unduly and also — Richard would want to say — unnecessarily impoverished by the extent to which they have gone for the statistical and the empirical and the axiomatic rather than the historical or the contingent. And so, this is a book which tries to redress that balance. It was accepted by the Cambridge University Press and again our editor, whom I already mentioned as the third in this great triumvirate of editors I’ve worked with in the past — first, Jeremy Mynott, and then Richard Fischer, and now Elizabeth Friend-Smith. She is the editor of the book, which is now at proof stage with Cambridge, and we hope will be out at the very latest at the beginning of new year.

So, I would like to say a word about the book. What I will say, will sound like a vulgar advertisement. But I do have to say that I think Richard and I — again, Richard did more of the work here — we were lucky together to assemble a really stellar cast of scholars to address the question that I’ve mentioned. And indeed, we approached people who we felt fairly sure will take the view that there has indeed been an impoverishment of a range of cultural disciplines — to the fact that they’ve gone positivistic, they’ve gone anti-historical, they’ve gone pseudo-scientific. And we have 14 chapters. I can’t obviously go through them all. But they cover the role of history in relation to the understanding of law — that’s a very powerful chapter by Michael Levin because, of course, much law simply is precedent based and is historical, and his account of the historically minded as very important to the appraisal of law is very finely done. As well as law we have economics — a riveting chapter by Adam Tooze. And also a wonderful historical work by Sheila Ogilvy, Professor of History of Economics at Oxford, on serfdom, showing us how the phenomenon of self-based societies has a relevance for us. So law and economics, but also sociology, political theory, political science. And then in the humanities, also, we have several fascinating essays on the history of literature. One by a historian of literature, Pamela Clemit; the other by an expert on Shakespeare, Catherine Shrank at Sheffield, who has produced a dazzling essay on the absolute indispensability of an historical approach if we are to have the faintest clue what Shakespeare is talking about. I mean, how could it be otherwise, that a dense investigation of the culture of the time would enable you to give an account of what is going on in those great books? We also have philosophers in there, and the volume ends with a very fine chapter by Joel Isaac at the University of Chicago on cultural anthropology, where he talks about the turn to history in cultural anthropology and the enriching effect that that has had. And so we’re rather optimistic about the idea that we’ve reached a kind of rock bottom of anti-historicism in a number of these disciplines. And from the point of view of the people who have contributed to this book, the only way is up. So it’s an optimistic book, and it has some really fun scholarship in it. And I’m very pleased that Richard generously included me in the project.

This interview was conducted on 18 August 2022. An audio recording is available here.