As I write this, Britain’s ‘summer of discontent’ is being followed by an equally disaffected winter, with a walkout from 50,000 rail workers still not showing signs of slowing down and instead increasingly of being accompanied by further industrial action in other sectors. A combination of rampant inflation and falling real wages has led to the worst cost of living crisis for decades, and narratives of ‘quiet quitting’ and generational burnout are seemingly increasingly resonant.

Against this backdrop, it might seem like an odd time to write an article examining the merits of work. Yet, perhaps somewhat optimistically, the current situation could be seen as a good opportunity for a broader conversation about the conditions required for humane work and to expose the exploitative practices that should be condemned to the past.

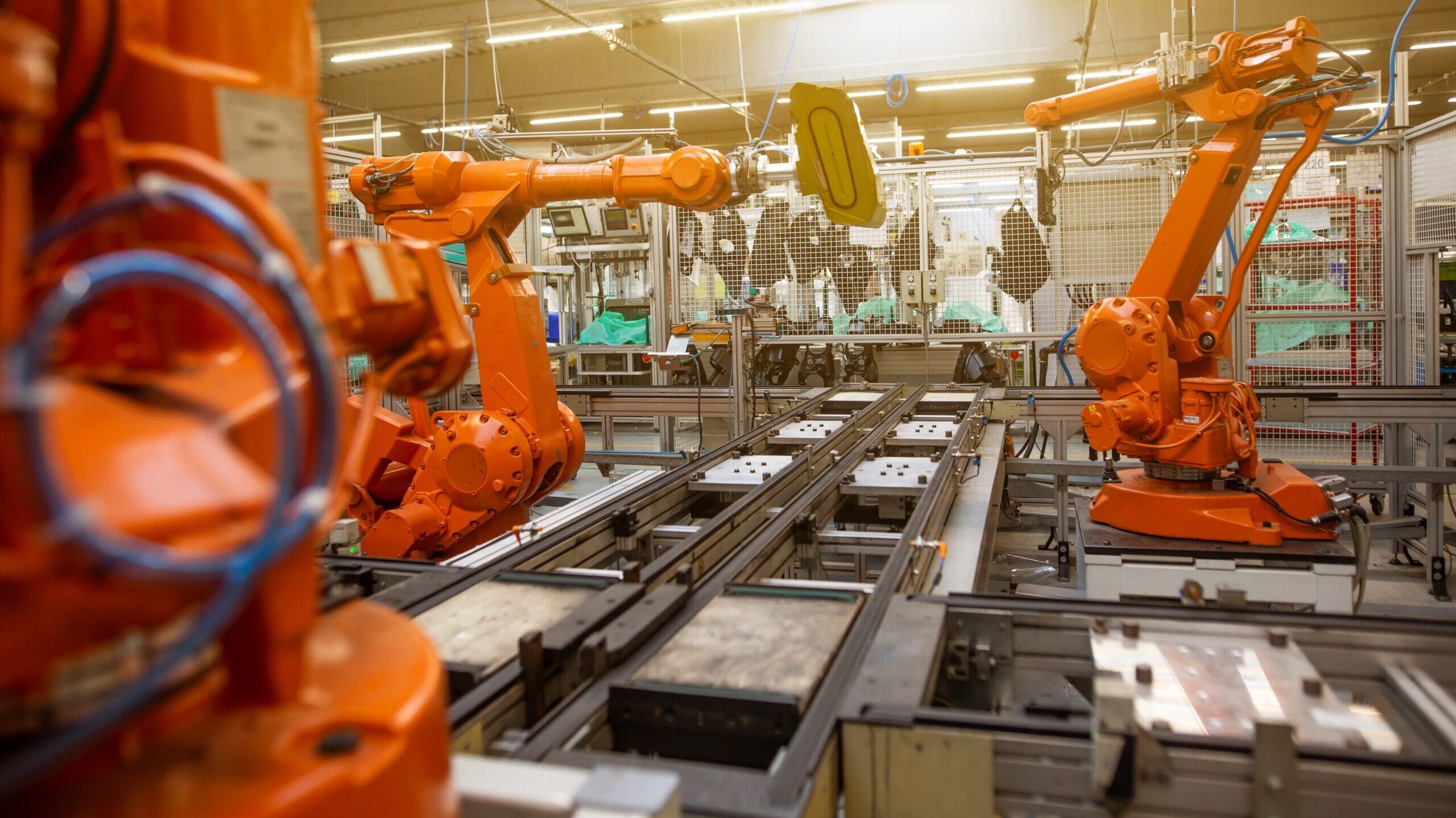

Any modern conversation about the future of work would be incomplete without considering the looming prospect of greater automation and its potential to irreversibly change large swathes of the labour market. The impact of these developments has been traditionally considered with regard to manual labourers (at least in the shorter term). More recently, however, the debate has shifted onto the terrain of creative work owing to the growing power of image generation systems like OpenAI’s DALL-E 2 and (the open-source) Stable Diffusion. These programmes potentially allow for any image to be generated based on a text prompt, from a medieval painting of the WiFi not working to a photograph of an astronaut riding a horse. Those most optimistic about the tools have made bold claims about their ability to disrupt the art world, drawing parallels with the way photography revolutionised painting. Digital illustrators have already begun to feel the effects, whether in seeing copies of their distinctive style or facing increased competition in art contests.

Despite these advances, one might retain a degree of reasonable scepticism about the reach of automation, given the unreliability of previous predictions and the fact that the threat can perennially feel like a future concern. There are still well documented shortages of HGV drivers and manual labourers in the national economy, and not much sign of self-driving cars or robots filling those vacancies soon. The academic research on the topic is unhelpfully divided, with famous claims (such as that half of US jobs could be automated in the next twenty years) now the subject of increased dispute and with continual disagreement about which kinds of jobs are most at risk.

One does not have to buy into strong claims about the breadth of automation to make a debate about the value of work worthwhile (though the more bullish one is about such automation, the more pressing the debate becomes). It only needs to be true that automation will greatly change the labour market to be worth serious consideration, and it certainly does not have to be the case that we will be able to automate every job. Thinking about the value of work may even allow us to shape an increased number of new jobs. Previous examples of new jobs being created owing to technological development range from those in computer programming to design.

To help combat the ahistorical and crypto-normative nature of much debate around technology policy, an interesting place to begin for views on the value of work is political theory. Here, a (slightly schematic) distinction can be drawn between an anti-work and a pro-work camp. To those in the anti-work camp, the notion of a fulfilling job is oxymoronic; work is where we’re condemned to involuntarily toil during the week. It is only through leisure that we can divulge our personal and creative pursuits, to develop ourselves beyond our economic role.

This anti-work view has a rich intellectual history and can be traced as far back as one Biblical view of work in Genesis. Adam and Eve were created to care for the Garden of Eden before Adam disobeyed God and ate the forbidden fruit. God decries to Adam that ‘cursed is the ground because of you; in pain you shall eat of it all the days of your life’ and that only ‘[b]y the sweat of your face you shall eat bread, till you return to the ground’. Adam is then sent out of the Garden to toil for his livelihood, reaffirming the idea that work is an arduous activity performed as an unfortunate necessity.

In the socialist tradition, the notion that work is an exploitative practice to be transcended is well-documented, recently inspiring Sarah Jaffe’s powerful 2021 book Work Won’t Love You Back. In the book, Jaffe looks to cut through pro-work ideologies encouraging employees to ‘love what you do’, deftly revealing how such ideas can be used to hide real cases of exploitation. Rather than relying on speculation about the future impact of technology on work, Jaffe raises important concerns about how technology has already affected workers’ well-being, from those employed in precarious contracts in the gig economy to others implicitly expected to respond to emails during evenings and weekends.

The pro-work side likewise also offers many arguments of interest to current debates around automation. Those on this side nearly always argue that work can be a good thing, but not as it currently exists. One traditional way of arguing in favour of the value of work has been to show how it allows for the exercise of capabilities beneficial for human flourishing. Again, the socialist tradition is relevant here, most famously in the young Karl Marx’s evocative (though opaque) allusions to the potential of work to be fulfilling. This potential is not realised under capitalism, and in Marx’s famous manuscripts of 1844, he highlights the alienation of labourers from the product of their work, the manner in which they work, other individuals they work with, and their own nature. It is also suggested that this alienation can be overcome, though Marx was famously reticent to explain how this might be achieved.

Aside from in service of a hope that the reader might find this material generally interesting, part of the point of signalling some of the relevant intellectual history to current debates around the future of work is to show that these involve as many normative questions as they do empirical ones. Whether work is a good or a bad thing is a value judgement that cannot solely be made on the grounds of empirical evidence alone. Is the exercise of our creative capacities important for human flourishing, or is it necessarily a bad thing to do manual labour?

That said, answers to these normative questions often rely on empirical premises. If it was found to be the case that work could have a positive impact on people’s well-being, this would lend credence to the pro-work camp. Recent studies in economics and psychology are therefore of relevance.

Though results illustrating the detrimental effects of overwork and stress abound, pro-work proponents maintain that regular work offers access to certain important goods. In a 2010 study, Karsten Paul and Bernad Batinic found that employed people enjoyed a greater degree of structure over their time, the social contact involved in work, a sense of collective purpose and the process of being active. Another well-cited 2019 meta-analysis by Martin Biskup and others found that people often do report positive emotions at work, including being alert, interested and cheerful. Another common finding is that employed people have higher general levels of well-being due to being able to access more goods.

However, as John Dahaner highlighted in his 2019 book Automation and Utopia, the anti-work camp can accept the results of these studies without compromising their beliefs. Given that people spend so much time at work each day, it is naturally the main institution through which these positive experiences are had. This does not mean that, should we radically reduce the number of hours that people work in the future, they would not be able to substitute work with other activities that provide these benefits.

Although Danaher’s logical point is a clarifying one, further empirical research should be done to try to improve our understanding of what is currently distinctive about (some) jobs that allow employees to achieve important goods. It might just be important to set complex goals, or to socialise with different kinds of people, for example. Having answers to these questions can also help to lobby to ensure more jobs allow employees to have these experiences. Longer-term, these empirical findings can then help to inform a broader normative vision of future employment, for example by giving weight to the view that a particular property of work allows us to exercise a certain capacity or virtue.

Depending on what is found, thought can also then be given to how it might be possible to translate these goods into different social practices in the future, for example by pursuing fulfilment through hobbies rather than work. It may be that translating some of these goods is possible, but until there is more evidence that this is the case, I think it is reasonable to be sceptical about such a possibility. Having faith in individuals to self-organise and voluntarily engage in personal development seems to remain an optimistic view.

This broader conversation about the future of work that I have hinted at in this article also has important policy implications. Illustrating this point, in a 2021 report on ‘Positive AI Economic Futures’, the World Economic Forum drafted six possible scenarios that AI development could lead to, with a particular focus on the employment market. It showed that if we conclude that there is something intrinsically valuable about work that cannot be replicated in other areas of life, this has important policy implications. To achieve the vision of a society with fulfilling jobs, we could prioritise the development of AIs that support human labour and automate dull tasks, rather than those that completely replace humans. In contrast, if we find that there’s nothing intrinsically valuable about work, this has other implications, for example by encouraging the introduction of a Universal Basic Income that looks to replace the daily grind.