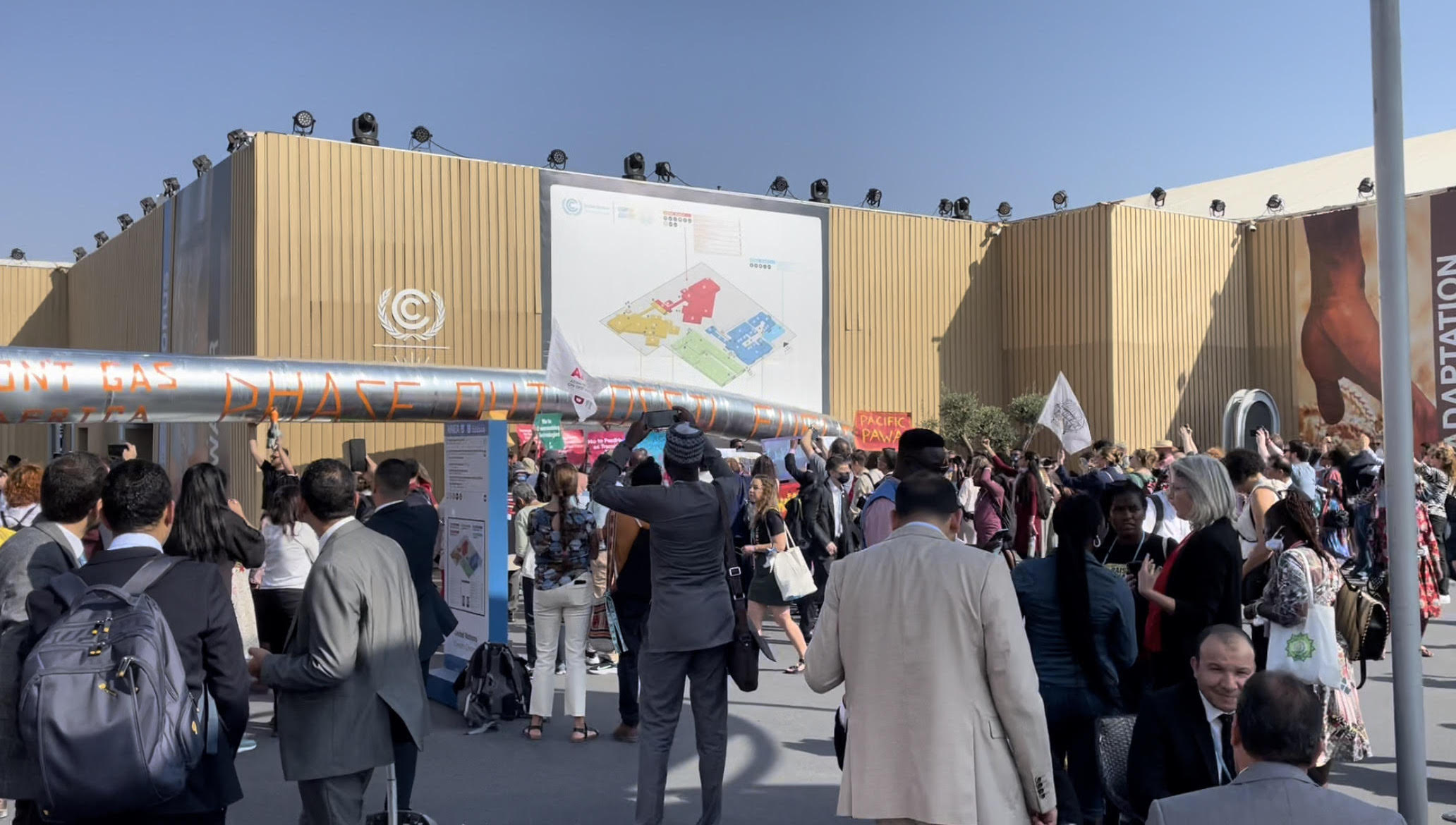

While nations were grappling to establish their interests in high-level discussions at COP27, grassroots organisations were vying for financial gains of their own in the conference hallways.

Dozens of small organisations, ranging from charities to activist groups to NGOs, were zealously lobbying and networking to make claims on the hundreds of thousands in micro-grants available to finance their environmental projects. COP, a venue teeming with environmentally-oriented groups, was fertile ground for representatives from organisations to connect with any potential donors they might encounter.

Many of these smaller organisations administer crucial services on the ground, such as providing relief for climate change-stricken communities, where larger organisations might lack local expertise. Yet securing funding can be an arduous exercise. There are demanding conditions they must meet in order to be considered for a grant, which prove to be consuming in both time and human resources.

Micro-grants are unpredictable, and there is intense competition for the few funds that these organisations are eligible for. The requirements and processes for applying for funds differ for each donor and intermediary, so organisations must tailor proposals to each source of funding.

This poses an even larger challenge for small organisations, as it requires them to invest in training their members on how to strategically bid for grants. Resources can be insufficient to maintain staff dedicated to this task, and organisations claim this directs money and efforts away from their environmental actions.

NGO funding is usually precarious. The vicissitudes of global politics and priorities of donors can suddenly leave them without reliable sources of financial support.

“We have UNICEF funding … aspects of our interventions, [however] we have a huge risk of having a single donor” shares Godwin Ade Tanda. Tanda is the Executive Director of the Environmental Protection and Development Association (EPDA), a Cameroon-based NGO currently working on food security and sanitation. Tanda has attended COPs in the past few years with the aim of appealing to potential donors. He refers to “conditions that are very hard for our organisation to meet” as barriers in securing funding, such as needing to “pass via a third party organisation.”

The unwillingness of donors to invest money into Cameroon is another obstacle, indicative of the additional difficulties in obtaining financial backing faced by organisations based in harder-to-reach areas. “With the socio-political crisis going on in the north-west and south-west regions of Cameroon, many people have been forced to move … Access to food, water and sanitation is a big challenge, and this is where we have [most] of our interventions.”

Indigenous groups at COP27 also advocated against the convoluted processes in accessing funds. According to the International Institute for Sustainable Development, 1.74% of global climate funding has been allocated to various Indigenous groups, but they only see 0.13% of this. While many Indigenous-run environmental organisations operate on a voluntary basis, Indigenous people officially manage nearly 40% of all protected areas and ecologically-intact ecosystems, as well as at least 12% of the world forest area (the real percentage is likely much higher).

The ambiguous status of Indigenous peoples on different continents can further complicate these efforts. According to Joan Carlin, Executive Director of Indigenous Peoples Rights International, “we are not recognised as Indigenous peoples, and our rights are not recognised. That has a direct consequence on our access to funds.” In Bangladesh, legally registering as an organisation in order to access foreign funds becomes difficult for Indigenous communities when their own legal status is contested.

The official funds for which these organisations are vying for include the $75m Green Basket Bond, which was established by financing institutions British International Investment and Symbiotics in 2022 to fund small scale green projects. Tanda hopes that more of the climate funding in the future can be directed towards frontline actors, especially those in middle income countries. However, organisations also hope to meet and convince representatives from companies or otherwise which may not be already funding environmental initiatives, but which are looking to expand their charitable activities.

The MacArthur Foundation, which finances climate action and the environmental activities of Indigenous groups, cites “four general approaches” that determine whether a climate-related initiative will receive funding. To begin, organisations must provide evidence for having “alter[ed] the political discourse”, but it is unclear specifically what this entails.

Despite these barriers, Indigenous environmental organisations are optimistic about the potential of a larger fund; specifically, the 1.7bn USD that was pledged at COP26 in Glasgow towards Indigenous groups tackling climate change.

If small environmental organisations on the frontlines of combating climate change continue to struggle to access necessary funding, populations suffering from floods, droughts, or other environmental disasters will be left to rely on government relief or larger, multinational organisations. While large organisations have their own role to play in addressing environmental issues, grassroots organisations are increasingly crucial. Ultimately, their main rallying point is their unique position in being more integrated and thus able to work with local groups and better understand the needs of their respective communities.