‘Wolf warrior diplomacy’—a common description of China’s combative diplomacy—does not wholly capture China’s economic diplomacy. Rather, China’s economic diplomacy reflects nuance. While Beijing does indeed boisterously blowback against offending corporations, this is not always the case. What makes this difference? Perceived strategic value. China displays harsher crackdowns on non-strategic goods while expressing caution towards strategic goods.

Released in 2015, the namesake Chinese action film, ‘Wolf Warrior,’ fervently espoused nationalist motifs, centring on Chinese G.I. Joe style fighters driving off Western mercenaries. As noted in Susan Shirk’s book Overreach: How China Derailed its Peaceful Rise’ and Peter Martin’s China’s Civilian Army: The Making of Wolf Warrior Diplomacy, upon the release of this film, the term was quickly adopted by Chinese diplomats and analysts, drawing comparisons to President Xi Jinping’s urging Chinese representatives to ‘unsheathe swords to defend the dignity of China.’ This has been reflected in widely publicized Communist Chinese Party (CCP) crackdowns on both foreign and domestic companies that cross sensitive subjects for ‘hurting the feelings of 1.3 billion people.’ As a result, ‘wolf warrior diplomacy’ has quickly become a popular term to describe China’s combative approach.

There is certainly an element of truth to China’s wolf warrior label. Examples of China’s approach to diplomacy range from publicly chastising the NBA into apologizing for its remarks on Hong Kong to organizing boycotts against the South Korean Lotte Corporation for permitting the United States and South Korea to deploy an antimissile system on its golf course. Some firms have learnt to accept and profit from China’s growing nationalism out of fear of missing out on the benefits associated with the country’s expansive market. In July 2020, luxury brand Coach released t-shirts with designs that inadvertently implied that Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan were not a part of China. Millions of Chinese internet users wasted no time attacking the high-end company for ‘insulting China’. Coach has since withdrawn the offending products from shelves and issued an official apology. Then, Coach went above and beyond by inviting Chinese celebrities to publicly promote “the motherland” at the China International Import Expo.

Despite these examples, ‘wolf warrior diplomacy’ is not an apt one-size-fits-all description of China’s economic and diplomatic strategy, particularly when describing China’s approach to specifically valued strategic goods. While tensions with the West persist, Beijing seeks to prop up the Chinese economy through expanding domestic production and stockpiling vital strategic goods. According to official publications, ‘resilience and security’ have been singled out by China’s economic institutions as the top priorities for 2022; specifically, authorities promise to safeguard the supply of food, energy, raw materials, industrial components and commodities. This is reflected in China’s top imports of 2022, which include mechanical and electrical products, high-and-new-tech products, fuels, integrated circuits and crude petroleum.

Because China prioritizes building up its domestic capabilities, Beijing does not retaliate à la mode ‘wolf warrior’ against key multinational companies producing key strategic goods. Beijing has targeted many Australian businesses with economic measures, including imposing high tariffs on Australian barley and wine exports in response to requests for an independent probe into the source of the pandemic from Canberra. Despite this, Australia’s iron ore mining industry, which accounts for the majority of its exports to China, remained unaffected. Due to the crucial significance of minerals and the dearth of serious alternatives to substitute for Australian iron ore exports, China’s restrictions did not effectively “penalize” Australia’s total export revenue. In 2020, Australia’s net exports of goods to China were valued at $145 billion, a decrease of just 2% from the previous year. This was largely owing to iron ore shipments, which more than compensated for tariff-hit wine, barley and coal exports. Given China produces just around 20% of the iron ore it needs, Beijing is disproportionately reliant on Australia’s natural resources.

Another important case study is the Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s trip to Taiwan, following which the Chinese government stopped importing Taiwanese citrus fruits and fish. Yet, Taiwan’s most valuable products, namely the semiconductors, were kept out of Beijing’s attempt to browbeat the island’s market economy, as China remains heavily dependent on Taiwan’s exports. In fact, striking Taiwan’s semiconductor sector would debilitate Beijing. Taiwan holds 64% of the world’s semiconductor manufacturing revenue, with Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) retaining the lion’s share of the market. Sanctioning Taiwan’s semiconductors would only impede Beijing’s technical ambitions and goals for manufacturing self-sufficiency. Rather than directly pressuring TSMC, China has devised incentives to entice Taiwanese tongbao (同胞 or compatriot) firms to relocate to the mainland, such as subsidized housing, preferential taxation, customs clearance, land use, and talent recruitment, among other forms of financial assistance.

As a result, China’s selective targeting of industries to challenge might suggest that, while Beijing weaponizes its market gatekeeping, Beijing is far more interested in sending a message to offenders than damaging its industrial priorities.

Despite this, Mainland China is determined to minimize its dependence on Australia and Taiwan. Recent actions by Chinese enterprises in Simandou, Guinea indicate Beijing’s ambition to investigate and diversify its iron ore supplies, given China’s significant reliance on Australian ore. Simandou may export 100 million tonnes of iron ore a year when fully developed, besting Australia’s Fortescue Metals Group Ltd Simandou’s ore possesses a higher iron concentration (65% versus Australia’s 60%), which translates into greater profits for miners. Recognizing this, Shandong Weiqiao Aluminum & Power Co Ltd , in recognition of this fact, joined an international consortium to help lead operations in Simandou. As part of its “Made in China” policy, Beijing has committed $1.4 trillion for investments in its semiconductor and high-end tech industries by 2025. According to Chinese government figures, integrated circuit manufacturing soared by 33% in 2021.

In fact, rather than adopting ‘wolf warrior diplomacy’ as an all-encompassing description of Chinese economic statecraft, a better characterisation contains two parts. First, China uses a “carrot-and-stick” technique, offering rewards and punishments to shape behaviours. “Wolf warrior diplomacy’ would fall under this category. Second, should China be unable to effectively use the “carrot-and-stick” approach toward key industries, it would quietly hedge itself through long-term divestment strategies.

This flexibility of China’s economic diplomacy points to how Beijing selectively decides to send nationalistic messages by punishing industries that pose less of a threat to the Chinese market.. In the meantime, Beijing withholds strong-arming tactics against key industries and builds its own capabilities. Perhaps once Beijing’s native capabilities in key strategic goods reach high levels of confidence, China’s economic diplomacy will evolve. Only then will China have the pluck to expand its economic targeting against former key resources.

Margaret Siu is a JD candidate at Harvard Law School where she currently chairs the Harvard Trade Forum. She previously studied at the University of Oxford and the London School of Economics as a Marshall Scholar, researching China’s strategic commodities and soft power. Brian Wong co-founded the Oxford Political Review, teaches Politics and is in their final year of DPhil in Politics at Balliol College, Oxford, and serves as Head of Strategy and Editor to Polemix, a Web 3.0 start-up.

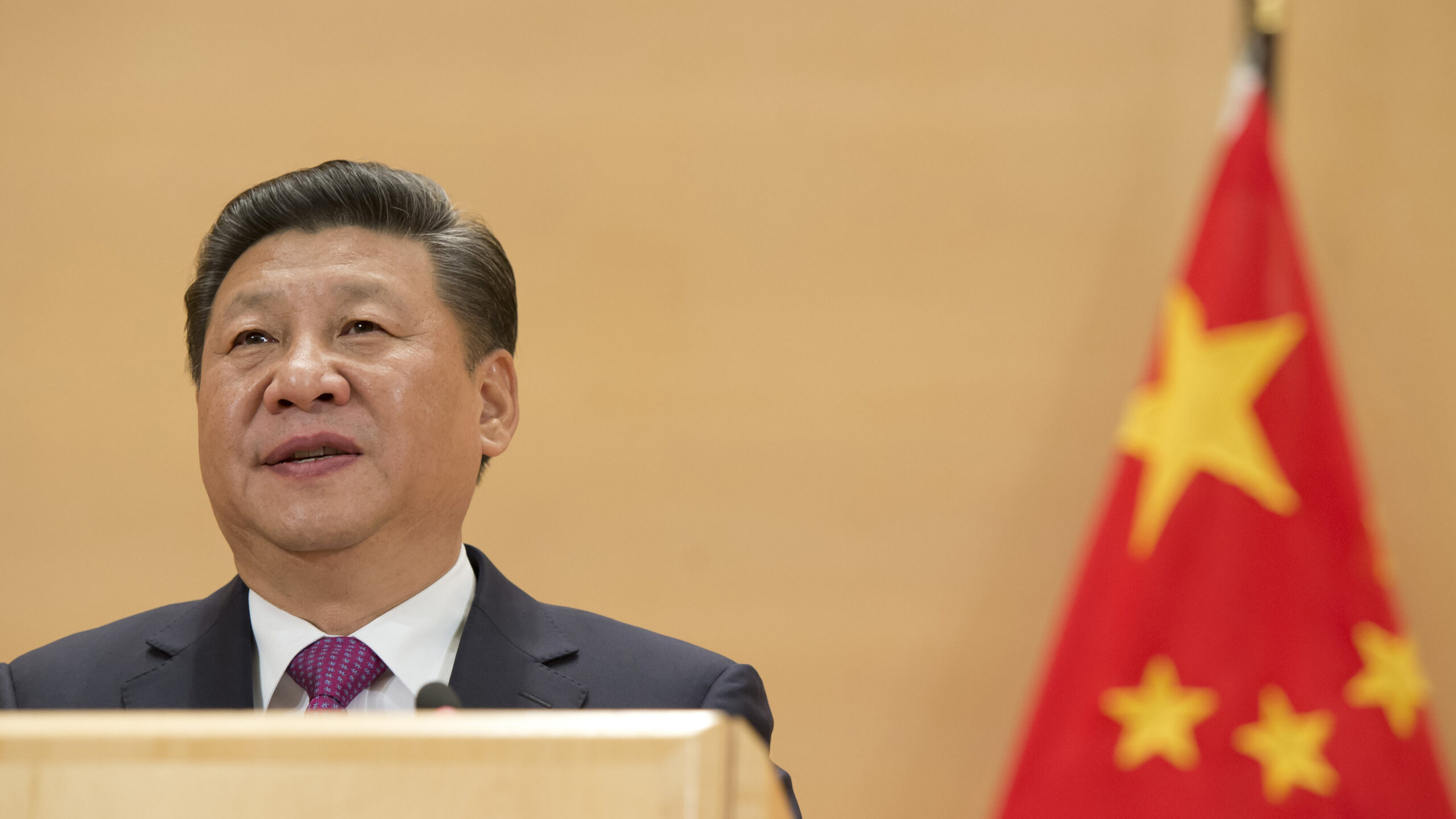

Image: Xi Jinping President of the People’s Republic of China speaks at a United Nations Office at Geneva. 18 January 2017. UN Photo / Jean-Marc Ferré.