The following article aims to analyse the involvement of the European Union (EU) as a peace mediation actor in Afghanistan. I argue that given the difficult conditions on the ground, the EU has made considerable achievements in its engagement in complementing the process, but that a completion of the Afghan peace process is yet not in sight. The piece builds on an interview conducted with the EU Special Envoy for Afghanistan, Ambassador Roland Kobia.

The argument is developed as follows: part I analyses the context of this conflict and the specific challenges; part II delves into the EU’s engagement and modes of involvement; part III explains why the completion of the process is immensely difficult; finally, part IV summarises the main findings and concludes with a brief outlook for the future of the EU as a peace mediation actor in Afghanistan.

I. A simple introduction to a complex conflict

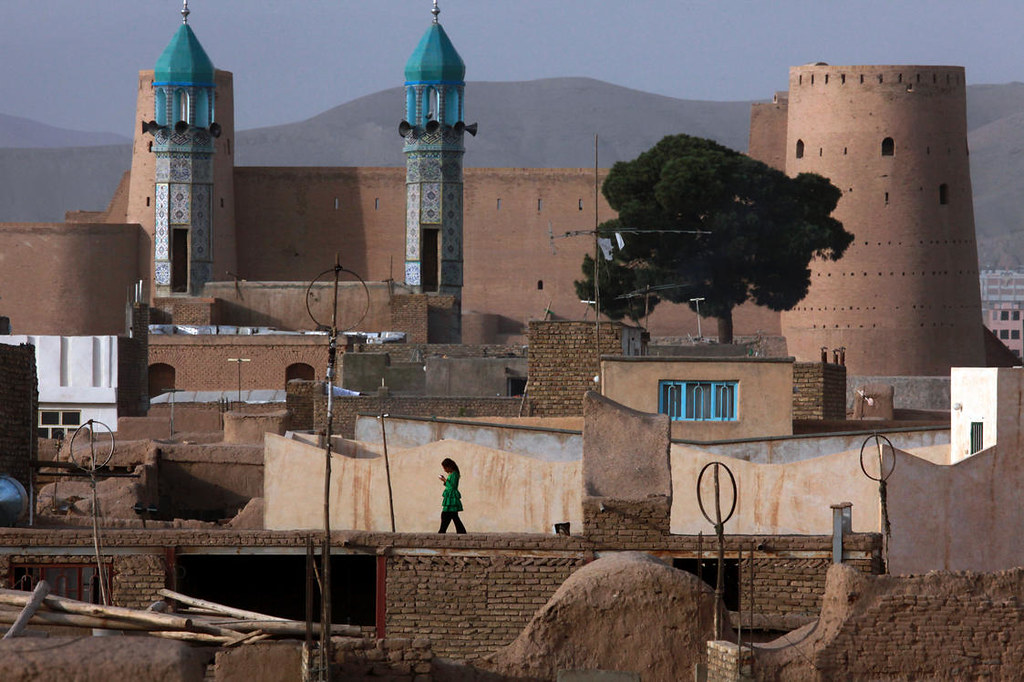

Afghanistan is a country that is “poor, ethnically diverse and marked by decades of conflict,” notably more than 40 years since the communist coup in 1978. After the regime of the Taliban in the 1990s, in the 2001 Bonn Agreement a new governance structure was negotiated, making Afghanistan a sovereign country with “fledgling democratic politics, and engagement with the international community.”

Yet despite the agreement, in the past 20 years, war has been waged between the Taliban on one side, and the Afghan government and international actors, such as the United States, on the other, recently reaching “a deadly stalemate,” with high death rates and casualties for all involved. After many difficulties, under US-support, the Taliban and the Afghan government finally agreed to open peace talks in Doha, Qatar, in September 2020.

The process has been called for by the whole international community to be an “Afghan-owned and Afghan-led process”; hence it is to be carried out, organised, and determined by the parties themselves: On the one side, the delegation of the Republic, which gathers a number of different interlocutors, different political parties, civil society, women; and on the other side the Taliban, whose “stated goal for Afghanistan has been to re-create the Islamic Emirate that was overthrown in 2001.” The two parties are negotiating, have discussed the rules of procedure of the talks and the agenda, but not yet the substance. The process has proven difficult, with “on-and-off negotiations,” until at present, the Taliban have left the negotiating table and negotiations are thus stalled.

II. The EU complementing the Afghan peace process

Afghanistan is certainly “one of the most complex conflict settings the EU has engaged in through its Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP)” and a “range of political and economic instruments.” The EU has made various commitments in the region. It aims to support the local population “in their path towards peace, security and prosperity in the long term.” Through acts such as the EU Strategy for Afghanistan 2017 (“strengthening the country’s institutions and economy”) and the Cooperation Agreement 2016 (“developing a mutually beneficial relationship” in the areas of “rule of law, health, rural development, education, science and technology, the fights against terrorism, organised crime and narcotics”), the EU aims to cooperate and assist the Afghan state in its rebuilding.

When it comes to the peace process itself, however, things become extremely complicated. The role of the EU is not quite clearly defined, as the mediation process is currently dysfunctional. The EU has a Special Envoy for Afghanistan whose role is “to lead and coordinate EU efforts related to the peace, stabilisation and reconciliation process in Afghanistan regionally and internationally” and to provide “support for an inclusive and Afghan-led peace process.”

However, in a telephonic interview with Ambassador Roland Kobia, he stated that the EU is not a mediator in the Afghan peace process, there is no mediation whatsoever on the Afghan peace process because it is a process between Afghans. For the time being the government and Taliban delegation are negotiating in Doha, but with no foreigners in the room, so there is no mediation. Of course, there is a number of countries and organisations, such as the EU, which are advising and helping and suggesting and taking positions around the negotiations, but there is no mediation sensu stricto and there is not even a facilitation.’

The EU has committed to provide financial aid to Afghanistan for the upcoming four years amounting to 1.2 billion Euros. But an important aspect to the role of the EU is that it does not act as a neutral actor in the process, given its strong commitments to build democracy and institutions in Afghanistan, to establish the rule of law, and to stress the importance of human rights and women’s rights. ‘The EU has taken positions on substance, on the end-state of these negotiations, which we would like to bring an Afghanistan to continue its efforts towards being a democratic country. We can try to remain impartial, which we are trying to remain, and we are critical of the Taliban, but also of the government when we feel it is needed. But the EU is not a neutral mediator’ (Interview with Roland Kobia). Being neutral in this setting, in this complex context of the conflict, would almost mean that EU would be willing to accept any outcome of the negotiations, which is not the case. The EU, in fact has a clear position: ‘What we do is that we keep dialogue open with both parties, even with the Taliban, and we tell them what our position is on the peace process. (…) We have a very principled stance on the defence of rights, fundamental freedoms, the republic, women, civil society, democratic efforts in general, and we have taken a very strong stance on the opposite way against a return of a regime like the one we have seen in the late 90s’ (Interview with Roland Kobia).

The EU has developed a number of concrete initiatives to support and strengthen the role of civil society in the negotiations on the government side, thus, on Track III. An example is the Afghan Peace Support Mechanism (APSM), which is financed by the EU, with some implementing partners from Sweden. The aim is to help civil society organisations generate input to the negotiating table. It is an example of concrete actions that are being taken to protect the space for civil society as well as to contribute to state-building. As the impression stands that the Taliban are not particularly interested in taking into account the civil society, the EU aims to push such initiatives, in order to prepare for the government side for the negotiations, and to ensure that it is empowered.

One of the most important aspects of the EU complementing the peace process is its commitment to the inclusion of Afghan women, who receive EU support. The issue of inclusion of women goes well beyond Afghanistan, of course, as the EU has a policy of promoting women’s rights and women’s empowerment across the globe and in peace mediation. Afghanistan represents a particularly important case for this policy, since the society remains rather conservative where women still need to find their place. According to Women for Women International, “Women in Afghanistan face pervasive insecurity, lack of livelihoods, educational inequalities, threats of sexual violence, and poor health and well-being” and in general, it is claimed that Afghanistan is “still the worst place in the world to be a woman.” Through the APSM, the EU is supporting the presence and power of female negotiators that are in the negotiation team.

In sum, the EU is taking various steps to complement the peace process in Afghanistan. Engaging also in public diplomacy and taking concrete actions on the ground, it is advocating for an inclusive peace process, with an emphasis on human rights and the rule of law, a strong civil society, women in the peace negotiations and in government positions, and an empowered Republic to negotiate with the Taliban.

III. The EU completing the process?

At present, as clarified above, the EU is not a mediator in the Afghan peace process, because the negotiations involve only the government and the Taliban, and no third parties (except in “hosting and supporting roles”). In general, a neutral mediator could be highly beneficial to the negotiations. Certainly, it “does not guarantee success”, but it could be highly beneficial to the negotiations. Overall, peace mediation could offer “a real and cost-efficient alternative to coercion, be that military intervention or power-based approaches that give little decision-making power to conflict parties (…).”

There are several challenges in the process, notably the reconciliation of two opposite visions of the future of Afghanistan: ‘(…) you have two visions of Afghanistan, the government and the Taliban, that are so far apart from each other in terms of the political government and the vision they have for their own country. So it is going to be extremely complicated to reconcile these two agendas and these two objectives, because you hardly can find any fundamental convergence between the two’ (Interview with Roland Kobia). There are a few things on which the two seem to agree, for example the sovereignty of Afghanistan or its independence. But when it comes to more concrete issues, such as what political system, what is the place for women, what are the fundamental rights, who decides, an emir or an elected government, they are at odds with each other.

Next to the short-term challenge of achieving a ceasefire, stopping the targeted assassinations and the terrorist attacks, and getting the Taliban to abide by the Doha agreement and by their commitments, it will also be important to build peace over a longer term. This might constitute a major challenge, as the end-state or output of the negotiations remains uncertain. Again, a negotiated political settlement will be very complicated to achieve, because it will need lengthy and difficult negotiations to find a middle ground between the parties.

Certainly, the EU has considerable power and influence in the context, as it is an important donor to Afghanistan and a “respected values-based global actor.” But because of this role as normative power, and also because of its own security interests, the EU is not entirely neutral and will attempt to stir negotiations in a certain direction: ‘What the EU will of course do is to try to support the efforts of this mediation. But in a certain direction, because we are not hiding that we have an agenda for Afghanistan, for the region, for the stability and security in the region… We also have an interest to secure the safety and security of Europe. In avoiding terrorist attacks from Afghanistan, drugs and narcotics reaching Europe from Afghanistan, human trafficking, export of radical ideologies, etc. So we have an agenda for Afghanistan, for stabilisation for the Afghans, but we also have an agenda for Europe. And we are trying, in the peace process, to defend these two interests at the same time’ (Interview with Roland Kobia). Hence, the EU has its own clear stance on the process, with clear goals and concerns, also for its own security.

Since the EU is not perceived as neutral, at least by the Taliban, it is unlikely that it will be appointed as a single mediator. However, as EUSE Ambassador Kobia noted in our interview, the EU might become part of a group of mediators. Not only is it considered an important international power and has experience in peace mediations. Crucially, the Afghan government is aware of the bias of the EU towards it which may lead to it favoring the EU over other potential mediators. In such a ‘group of mediators’, each side would have the opportunity to appoint mediators, which would lead to a balanced process and satisfaction on both sides: ‘Maybe the EU can be part of a group of mediators, where you will have some mediators that are more pro-Taliban and some mediators that are more pro-Republic’ (Interview with Roland Kobia). Moreover, the EU might even be one of the most important actors to be considered as a mediator by the Afghan government: ‘Let’s say, each side decides to appoint two or three mediators each, then the EU would certainly be appointed by the government, because the government is, of course, extremely happy with our positions. And if they had to make a choice, if they had a free choice to appoint mediators, I think the EU would probably be the first, the very first, to be appointed by the government. So that is a solution, to appoint a group of mediators. And then the EU would be ready to play its role and to take its responsibilities’ (Interview with Roland Kobia). Given that finding a single mediator that would be acceptable to both sides is likely very difficult, precisely because of the divergence in the parties’ positions, a group of mediators could be a potential avenue for the EU to play a role in the completion of the Afghan peace process.

IV. Conclusion

This article has attempted to explain the complexities of the conflict in Afghanistan and the difficult peace process to end it. In sum, it can be said that the EU plays a considerable role as donor to the Afghan government, in supporting various initiatives to empower the state and its civil society. The EU also supports the peace process as such, but it does not act as a fully neutral bystander who could be accepted by both parties as a single mediator for the process. However, the fact that the EU is not neutral does not exclude the option of having it being part of a group of several mediators to complete the peace process: ‘Everybody favours someone in this process (…). If we manage to bring together a number of mediators who have different views they can maybe try to help the process’ (Interview with Roland Kobia).

The article has also attempted to explain why finding a solution on substance can be difficult, since the two visions of the parties for Afghanistan lie far apart and the Taliban have currently even left the negotiation table. What is clear is also that a solution must be found, because the situation on the ground is highly concerning: ‘There is terrible violence, not only the quantity but also the quality, the brutality. The killing of civilians and journalists, trying to prepare the ground for a final takeover of the capital. Afghans are suffering tremendously’(Interview with Roland Kobia). Therefore, no matter the difficulties and the challenges involved, the EU has to continue advocating for a negotiated short- and long-term peace in Afghanistan: ‘We need to continue, we need to be resilient, and we need to be stubborn’ (Interview with Roland Kobia). The EU will thus continue to complement the peace process as a peace mediation actor, and it should also attempt to contribute to its completion.

Julia Vassileva holds an MPhil in International relations from the University of Oxford, a law degree from the University of Vienna, and an MA in EU International relations and Diplomacy studies from the College of Europe in Bruges, with a research focus on peace mediation and foreign policy.