Imagine yourself in a world, where the officials of the Pakistan Military Forces are enjoying scrumptious Sindhi delicacies, and just on the very opposite corner of the street, an impoverished Bengali child whose parents were mercilessly murdered by the Pakistan Army, is struggling to find a handful of rice for his only meal of the day. How would such an existence feel? This rhetoric is a strong representation of erstwhile East Pakistan till 1971. The twenty-four years of governance by West Pakistan were driven by immense level of discrimination towards the Bengalis and near complete marginalization in terms of resource allocations and growth.

The pre-1971 Pakistan government deprived the then East Pakistan province financially by allocating marginal budgetary allocations. Every other province of Pakistan, including Sindh and Punjab, used to get allocation in accordance with their area and population, but the Pakistan government never followed such a concept for East Pakistan. Segregation was evident and the Bengalis totally felt the sense of anger as these episodes of inequality and marginalization evoked the strongest of the emotions among them. Majority of the Bengalis in the eastern part of Bengal had favoured Partition and the establishment of a separate Muslim state with the ambition of living in an egalitarian society; idealizing a mechanism of governance inspired by the core principles and fundamentals of their history and democratic opinion. They believed that Pakistan would nurture a political ecosystem influenced by the virtues of religious values, naturally feeding into socio-economic betterment of the masses. Soon after the Partition, the people in the Eastern wing of Pakistan realized that their cultural heritage was under threat in their new country, with West Pakistan based ruling class not only attempting to forcefully impose ‘Urdu’ language on them but also creating hurdles to the growth of democracy and freedom of expression.

The Struggle for Bangladesh

The struggle for rights in East Pakistan started shortly after the Partition with the advent of two non-contiguous territories known as West Pakistan (today’s Pakistan) and East Pakistan (today’s Bangladesh) which were separated from each other by nearly a thousand miles. The refusal to accept Bengali as a state language of Pakistan in the early years after Partition, economic disparity between the two parts, the hegemony of the West Pakistan ruling elite over the entire country, dictatorial martial laws, and a demeaning attitude towards the Bengali culture and the Bengali population in entirety soured relations between the two wings.

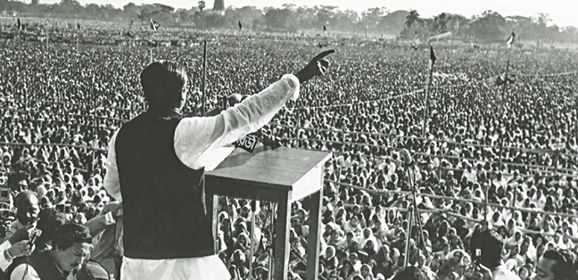

Political crisis was only a matter of time, and the death of democracy became evident by December 1970 when despite the Awami League (led by Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman) winning the elections, political groups based in West Pakistan, specifically the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) led by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, refused to hand over the power. Even after securing a clear sweep victory, the Awami League was not allowed to form a government. The Pakistan Army soon started taking steps to constrain the growth of nationalist sentiments and the ideology of freedom in the east. Rather, it decided to recruit local Biharis and pro-Pakistan Bengalis, including members of the organization, Jamaat-e-Islami (with its parent institution in Pakistan), for its violent and ruthless operations against the Bengali thinkers and activists.

In the midnight of 25th of March 1971, the Pakistani Army enforced the infamous ‘Operation Searchlight’, which led to the loss of lives of intellectuals such as notable university professors,

celebrated authors and filmmakers, politicians, activists, college students and countless other innocent civilians. Pakistan started a systematic purge of Bengalis.

Even after the official ending of the war on 16 December there were reports and news of killings being committed by either the armed Pakistani soldiers or by their collaborators. Just two days before Pakistan Army surrendered, on 14th of December 1971, the Pakistan Armed Forces along with its local collaborators conducted mass murders of intellectuals, who could have played potential roles in re-building the nation after independence.

On 26th March 1971, the provisional government of Bangladesh was declared, marking the start of the Liberation War of Bangladesh by Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. On 10 April, the Provisional Government of Bangladesh issued an announcement on the basis of the declaration and established an interim constitution for the movement of independence. The massacre resorted to by Pakistan’s soldiers in East Pakistan in 1971 was a panoramic continuation of the murder and havoc which the Indian sub-continent experienced in 1947. The military aggression on Bengalis lasted for a total time span of nine-months and in such a short duration, the Pakistan Armed Forces and its local allies killed more than three million people and hundreds of thousands of women were sexually assaulted by them: war crime was rife in 1971. Gradually, the forces in favor of an independent state of Bangladesh started liberating distinct parts of Bengal. On December 16, 1971, almost 100,000 Pakistani soldiers surrendered in Dhaka, leading to the creation of the sovereign nation of Bangladesh. This was the biggest surrender of any military force after the Second World War. Since then, the relations between the two countries have remained frosty for the past 49 years.

However, post-Independence, the Bangladesh government placed three specific demands to the government of Pakistan, several times in front of the international community and in various bilateral or multilateral meetings. The demands were: 1) unconditional apology for committing genocide during the war; 2) repatriating the Pakistani citizens stranded in Bangladesh; 3) payment of the money that actually belonged to Bangladesh. In this past 49 years, Pakistan has not agreed to any of these terms. Nor did Pakistan present any diplomatic gesture to meet the demands of Bangladesh.

At the peak of genocide, the local members of Jamaat-e-Islami were equally partisan in killing fellow Bengalis but when some of the perpetrators who were influential figures in the political spectrum of Jamaat-e-Islami were subjected to capital punishment in accordance to the basis of International Crimes Tribunal (Bangladesh), the reaction was at best frowned upon by distinctive politicians and lawmakers of Pakistan.

Tryst with Secularism: Has Bangladesh emerged as a Secular State?

In historical context, the articulation of secularism as the basis of the new state was met with a broad range of mixed views in Bangladesh. In 2010, Bangladesh Supreme Court declared the 5th amendment illegal and restored secularism as one of the basic tenets of the Constitution. Besides, Islam remained to be the state religion in the constitution. When political parties in their manifestos want to change the structure, system of government, judiciary and laws of the state in conformity with the principles and beliefs of a particular religion among multi-religious citizens, people of other faiths in such a state perceive gross discrimination on the basis of religion. Such discrimination is arguably untenable under the Bangladesh Constitution. However, in the past few years, secular writers and activists have been attacked by extremist groups.

Lastly, one of the most influential political parties of the country, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), has been widely criticized for its empathy and tolerant stance regarding the objectives of the religion-based organization, Jamaat e Islami. In January 2013, Bangladesh’s High Court declared the

registration of Jamaat-e-Islami to be illegal, banning it from contesting 2013 general elections. The court made the ruling in the country’s capital, Dhaka, after a petition was lodged arguing that Jamaat’s charter breached the constitution. The politics of Jamaat and coup attempts by the army in various instances sparked chaos across the country in the past few decades. Besides, the acts of genocide which were aided by the members of Jamaat during the 1971 Liberation War, was utterly harsh and resembled cruelty. ‘Islam’ is a peaceful religion, and the attempts and actions taken by Jamaat in 1971, whatsoever does not fall within the nuances and integrity of Islam. Pakistan should pay reparations to Bangladesh At the end of a war, countries involved are required to make payments as a framework to cover up for the damage inflicted during the war. This was the case when World Wars I and II ended.

The Case for Reparations

In reality, the debt, in the form of reparations can be paid back for a number of reasons, including machinery alteration and infrastructural damage, loss of lives, forced labor or for various different forms of war crimes. Typically, compensation comes in the form of money or material goods. When the World War II came to an end, Germany was required to pay the most, however, the original total still appears unclear – mainly because Allied countries demanded different forms of repayment at different bilateral or multilateral meetings and in various conferences to discuss Europe after the war. It was subjected to pay reparations to the winning side, due to the damage and infrastructural collapse caused during the Second World War. The notion and argument in relation to the context of 1971 could be similar.

Pakistan should pay reparations to Bangladesh. According to government estimations, the Tk18,000 crores that Pakistan owes Bangladesh includes amount from the wartime reserve of undivided Pakistan, as well as that on cyclone relief. In 1970, $200 million fund that came as donation for East Pakistan in the form of relief materials and cash from different countries after cyclonic storms hit East Pakistan were never delivered. That natural disaster, equal in intensity to a category three influential hurricane, took more than half a million lives in the coastal areas of Bangladesh. After independence, the Pakistan government said it could not send the money because the war began. However, according to constructive evidence and empirical data, that claim cannot be true. The cyclone appeared in November 1970 and the Liberation War began on March 26, 1971, which means that the West Pakistani rulers got approximately four months to pay. No money was spent on rebuilding any of the damaged infrastructure, neither were any relief materials distributed among the people affected by the hurricane. The money was initially kept at the Dhaka (then Dacca) branch of the State Bank of Pakistan and was later transferred to the bank’s Lahore branch during the war. This itself could be regarded as the first gesture of Pakistani government of not paying the money which Bangladesh indeed deserves.

It is not a matter of denial that Bangladesh deserves reparations and an unconditional apology from Islamabad for all the calamities Pakistan had caused in 1971. Reparations and an unconditional apology from Pakistan are still possible, and they have to be done through mutual understanding between the two states. The task is difficult and the possibility of a positive outcome is still very low. Pakistan has never been an ally of Bangladesh, so the task is indeed difficult and legal battles take time and there is no certainty of success. Moreover, the United Nations is not known to have ever played any roles in such cases. Today, Bangladesh is proudly presenting an exemplary feat in front of the International community by hosting more than a million Rohingya refugees on one hand, and being a leading exporter of Ready-Made Garments on the other hand.

Despite falling in distinctive situations in terms of military coup and instances of corruption, economic growth and prosperity is evident in this country. Diversity and inclusion are cherished ideals, and the current institutions are operating with a much greater level of accountability and efficiency than the pre-1971 era. In these 49 years, in many instances, the ‘journey’ of Bangladesh has been beautiful. However, we can surely be hopeful, that the ‘destination’ of Bangladesh of become self-reliant in its developmental trajectory would turn out to be as beautiful as the journey itself.

Md Nazmus Sakib Khan is currently an A’ Levels student at Mastermind English Medium School, Dhaka, Bangladesh