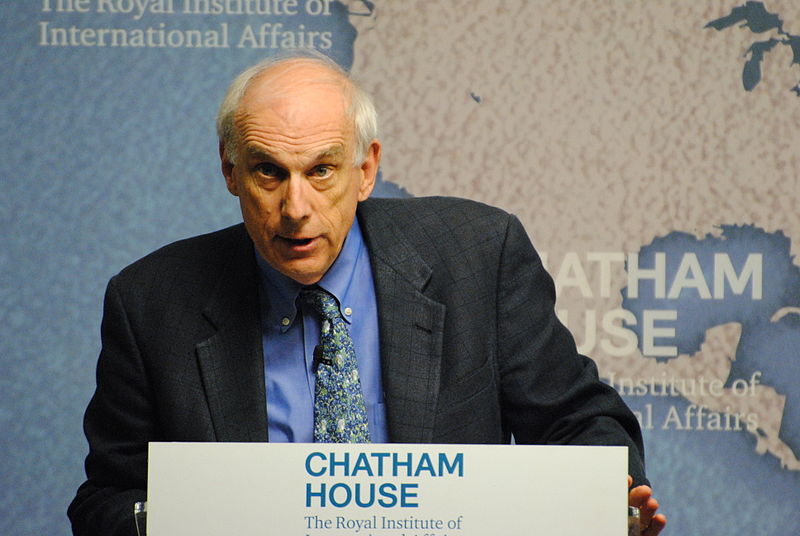

Brian Wong spoke to Robert O. Keohane, Professor of International Affairs, Princeton University. He is the author of After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy (1984) and Power and Governance in a Partially Globalized World (2002).

MULTILATERAL INSTITUTIONS. I have a controversial suggestion here – that much of such resentment and backlash has to do with the perceived inequalities and exclusionary nature within multilateral global institutions, and thus the root cause lies within the modus operandi of globalisation. What do you make of this suggestion, and – more generally – the interactions between domestic and international politics?

The first thing to realize about multilateral institutions is that they are run by states. As I have argued, they are valuable tools for states but they reflect, not override, state interests. If states are run by elites that are exclusionary and foster inequality, multilateral institutions will be exclusionary and foster inequality. Viewing multilateral institutions as if they should be ideal and operate according to idealistic principles, and then becoming disillusioned because they are responsive to state power ,and the interests of elites who run states, is naïve. My teacher, Stanley Hoffmann, spoke of “good will without illusions.” We need to try to make IO’s more responsive to good values as well as more effective, without expecting them to transcend or transform politics. In other words, political realism and support for multilateral institutions are complementary, not opposed ideas as the stereotypes often assume.

GLOBALIZATION AND CAPITALISM. “Those of us who celebrated globalization for its impact on overall prosperity and peace did not sufficiently take these economic nowand political effects into account.” What do you think accounts/accounted for the blind spots within the theoretical sphere? Presumably the presence of both defensive and offensive interests (especially clashes over geopolitical disputes and economic interests) had persisted after World War 2, so I’ve always been a tad curious and baffled by the extent to which the scholarly community took fervently to globalization.

Could the issue lie less with globalisation, than with the particular, capitalist form and manifestation through which it occurred? Could there have been room for a form of globalisation without capitalism?

This is a great question. My issue with globalization – see my article in Foreign Affairs, spring 2017, is that it was captured by corporations and their lawyers. Another way of expressing this would be say that it was corrupted by capitalism. I don’t know the answer to your question. It may not be answerable but it would be worthwhile to pose the questions comprising it clearly. How do you define capitalism? What would a non-capitalist economic system look like? Where would power lie in it? What would the interests of powerful actors be – would they favor globalization, and if so in what form? As usual in the analysis of politics, start with interests and power and think about how they affect, and are affected by, institutions.

CLIMATE CHANGE. Is it not too late to try stall or prevent climate change through de-carbonisation? Perhaps the answer to Climate Change is to massively invest in adaptation – as opposed to futilely pursuing de-carbonisation? (I ask, as I am massively sympathetic to the argument you make about buying us more time, but am channeling a worry that many cynics do have towards de-carbonisation efforts).

The premise of this question – that we have to choose between adaptation and decarbonization – is false. We obviously have to adapt to the climate change that has already existed, but if we are to avoid change on a scale to which we cannot adapt, we need to decarbonize. False alternatives are the bane of much commentary avoid them.

Are you interested in getting involved directly with the climate activist movement? I ask, because I think much of your insights could be incredibly valuable in aiding the strategisation and programme development of the activist prong of the climate change movement.

One of my friends and former students is trying to persuade me to do so. I doubt that I have much comparative advantage in doing this, so I think that my involvement is better indirect – many young activist academics are familiar with my ideas and are using them in their own work.