Ever since Chinese President Xi Jinping’s announcement of the ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ in 2013 raised disapproving (or perhaps jealous?) eyebrows in the west, an insidious trend has emerged in relation to reporting on China within western media circles. Scaremongering articles, complete with ominous headlines such as ‘What China is really up to in Africa’, have rushed to portray China as the new face of neocolonialism in Africa. Analysts point to the $95.5 billion loaned by China to various African countries between 2000 and 2015 as proof of a nefarious policy of ‘debt-trap diplomacy’ (a type of diplomacy involving one creditor country extending excessive credit to a debtor country with the intention of extracting concessions) and commentators regularly speculate gravely about China’s supposed hegemonic intentions.

The reality of Chinese coercion through high-interest loans, especially when it culminates in the acquisition of foreign lands (eg Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port), is rightly perceived as a global cause for concern. Nonetheless, current media focus, and I daresay overemphasis, on Chinese neocolonialism is ultimately unhelpful. This is because fixating on the narrative of harmful Chinese involvement in Africa threatens to obscure the damaging economic and cultural repercussions of the legacy of European colonialism, both specific to Africa and more broadly. As Mark Langan convincingly argues, western actors tend to paint China as the sole perpetuator of ‘conditions of mal-governance and ill-being’ in Africa, ‘othering’ it from themselves (1), and thereby implicitly presenting neocolonialism as a novel and distant practice, detached entirely from the legacy of colonial rule. This conceals the vital fact that former European colonial powers, including Britain, also continue to facilitate their own economic and political interests via intervention in former colonies, equally to the detriment of African sovereignty.

To understand how neocolonialism functions, a useful starting point is ‘dependency theory’, the idea that resources flow from a ‘periphery’ of poor and underdeveloped states to a ‘core’ of wealthy states, enriching the latter at the expense of the former. Che Guevara in 1961 made the critical link between the economic mechanism of neocolonial control outlined above and the legacy of colonial rule: regarding Cuba, though his point is just as applicable to former colonies in Africa, he stated: ‘we, politely referred to as “underdeveloped”, in truth … are countries whose economies have been distorted by imperialism’. The ‘distorted development’ experienced by former colonies following their independence has in most cases brought about dangerous over-specialisation in raw materials or a single crop. Cuba, to take Guevara’s example, has always relied heavily on sugar exports, and in the case of sub-Saharan Africa, World Bank analysis in 2013 found that despite improved economic growth over the past decade, natural resources still accounted for three-quarters of the region’s exports. This situation of ‘chronic dependency’ was deliberately left in place by the occupying colonial powers to ensure that Africa remained a reliable source of natural resources for their industrial economies.

This is not to say that the export of raw materials from African countries to the west, and newly emerging economies such as China and India, is inherently problematic, but rather that the current system guarantees significant ‘leakage’ of profits back to the core via multinational companies. Africa is after all richly endowed with raw materials, most notably around 30% of the world’s known mineral reserves, and global demand for these resources is growing exponentially (mineral and oil prices have tripled in the last decade), theoretically presenting Africa with ample opportunities for profit. However, the uniquely exploitative brand of colonialism implemented by European powers has prevented former colonies from making the transition to sustainable growth and development even after independence, thus ensuring that they remain peripheral within the world economic system (2). As a result, contemporary neocolonial powers are still able to capitalise on African ‘underdevelopment’ by taking control of land and raw materials (mines) across the continent, but this time without going through the process of formal colonisation. We must, therefore, bear in mind when discussing neocolonialism that the current exploitation of former African colonies is in many ways a direct consequence of the economic repercussions of European colonial rule.

The extent of European entanglement in Africa, even in the present day, unsurprisingly tends to slip under the radar in the west. The charity ‘War on Want’, in pursuit of their aim to challenge the root causes of global poverty, published a damning report in July 2016, revealing both the degree to which British companies once again control Africa’s key mineral resources and the vital role played by the UK government in ensuring that these companies gained access to the raw materials. According to this report, 101 companies listed on the London Stock Exchange, most of them British, have mining operations in 37 sub-Saharan African countries; collectively they control over $1 trillion worth of valuable resources, and, aided and abetted by our government, have extracted $192 billion from Africa, a state of affairs described by director John Hilary as a ‘new colonial invasion’.

While this scale of plunder is frustratingly predictable from companies with environmental degradation and labour abuse records as soiled as Glencore and Rio Tinto, the involvement of the UK government is more troubling, especially considering how easy it is for us to delude ourselves into believing that post-colonial western intervention in Africa has been on the whole beneficial, or even necessary. The tendency to dress up British investment in African countries as aid, benevolently given with noble intentions, is simply a continuation of the colonial paternalist narrative, and therefore another consequence of the cultural legacy of European colonialism.

For example, the government, and by association we as citizens, applaud ourselves for spending 0.7% of our GDP on aid, and on the surface there seems no reason why we shouldn’t; it is after all possible to do a huge amount of good with ‘0.7% of GDP’ worth of aid. However, even if the failures of numerous aid policies in terms of alleviating poverty are put to the side, digging into the intentions behind that aid, and British foreign policy objectives more broadly, brings up more red flags. The declassified documents outlining post-war British foreign policy in relation to Africa demonstrate that the British government continued to perceive the entire continent through an imperialist lens, primarily as a source of raw materials. For instance, Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin noted in 1948 that there was a need to ‘develop the African continent and to make its resources available to all’, a sentiment similar to that expressed by a Cabinet Office study from 1959, which noted that one of Britain’s two most important interests in Southern Africa was to develop trade and guard access to raw materials. In preparation for the then-inevitable process of formal decolonisation, ensuring that the economic and political climates in African countries were favourable for exploitation by British companies was an important economic priority in the aftermath of the war.

These overt neocolonial aims remain a convincing explanation for British policy in Africa today. For example, the ‘High Level Prosperity Partnerships’ scheme launched by the Department for International Development (DFID) in 2013 essentially used the promise of aid (‘access to British expertise in financial services and education’) as a bargaining chip to secure access to African raw materials for British oil and mining companies in 5 African countries. Coupled with Priti Patel’s comments as International Development Secretary in 2016 promising to ‘leverage’ foreign aid to strike trade deals, it becomes increasingly blatant that Britain has continued to intervene throughout Africa in pursuit of its own economic interests, deliberately operating as a neocolonial power and exploiting the continent’s raw materials under the guise of providing mutually beneficial aid.

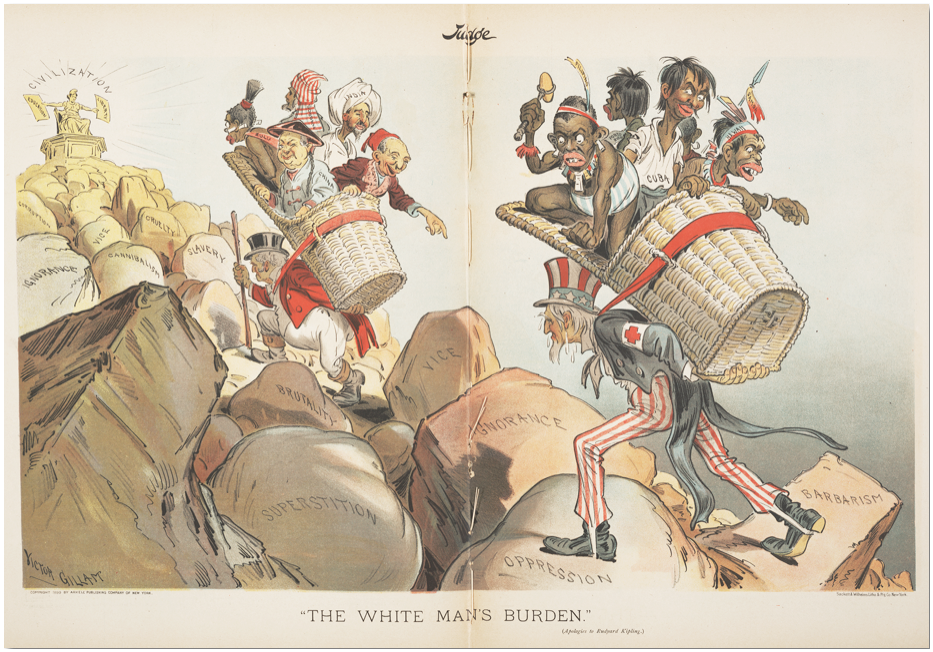

Why then have we been so quick to condemn Chinese investment in Africa as destructive and immoral, when for all intents and purposes Britain has engaged in similar practices, only disguised as aid? Again, this double standard can and must be traced back to the problematic cultural legacy of European colonialism. Proponents of European imperialism at the time typically regarded native cultures with disdain and presented colonisation as a beneficial ‘civilising mission’, an act of charity aimed at uplifting the ‘uncivilised’ natives rather than an act of direct exploitation and domination. Fiction during the period, particularly the works of Rudyard Kipling, also helped to spread the perception that colonised people were incapable of surviving without the help of Europeans: Kipling’s infamous poem ‘The White Man’s Burden’ (1899) romanticised British colonialism, idolising western culture as entirely rational and civilised while treating non-white cultures as childlike and demonic (3). Consequently, at a time when many people are (rightly) growing increasingly dubious of American foreign intervention, British investment and aid in Africa continues to be broadly perceived as at the very least well-intentioned, regardless of the extent to which it mirrors supposedly unethical Chinese interference in Africa.

This paternalist colonial narrative, reinforced in western minds by the economic and political struggles which have blighted some former colonies since their independence, is today wielded implicitly by neocolonial powers in order to justify their continued intervention in Africa. Current prime minister Boris Johnson’s Spectator column in February 2002 entitled ‘Cancel the Guilt Trip’ exhibits some outrageous one-liners to this effect. Johnson went as far as to outright state that ‘the problem is not that we were once in charge, but that we are not in charge any more’, a frightening demonstration of the extent to which the notion of western superiority remains ingrained within our culture, or at least within the minds of our current political leaders. Evidently then, we still have a long way to go in terms of acknowledging and responding to the legacy of European colonialism.

Western media’s portrayal of China’s strategy in Africa as predatory and self-seeking, regardless of how truthful these accusations may be, smacks of narrative-building; an underhanded attempt to present colonialism as something far away in space or time. To avoid falling for the widespread myth that there exists a binary divide between altruistic western intervention in Africa and exploitative Chinese interference, it is vital that we perceive African development, and by extension Sino-African relations, through the lens of European colonialism and neocolonialism.

Bibliography

- M. Langan, ‘Neo-Colonialism and the Poverty of ‘Development’ in Africa’ (2017), pp.94-101

- K. Kalu, T. Faloya, ‘Exploitation and Misrule in Colonial and Postcolonial Africa’ (2019), pp.8

- J.Syed, F.Ali, ‘The White Woman’s Burden: from colonial civilisation to Third World development’, Third World Quarterly, 32 (2), pp.349-365