Anatomy of A Disaster

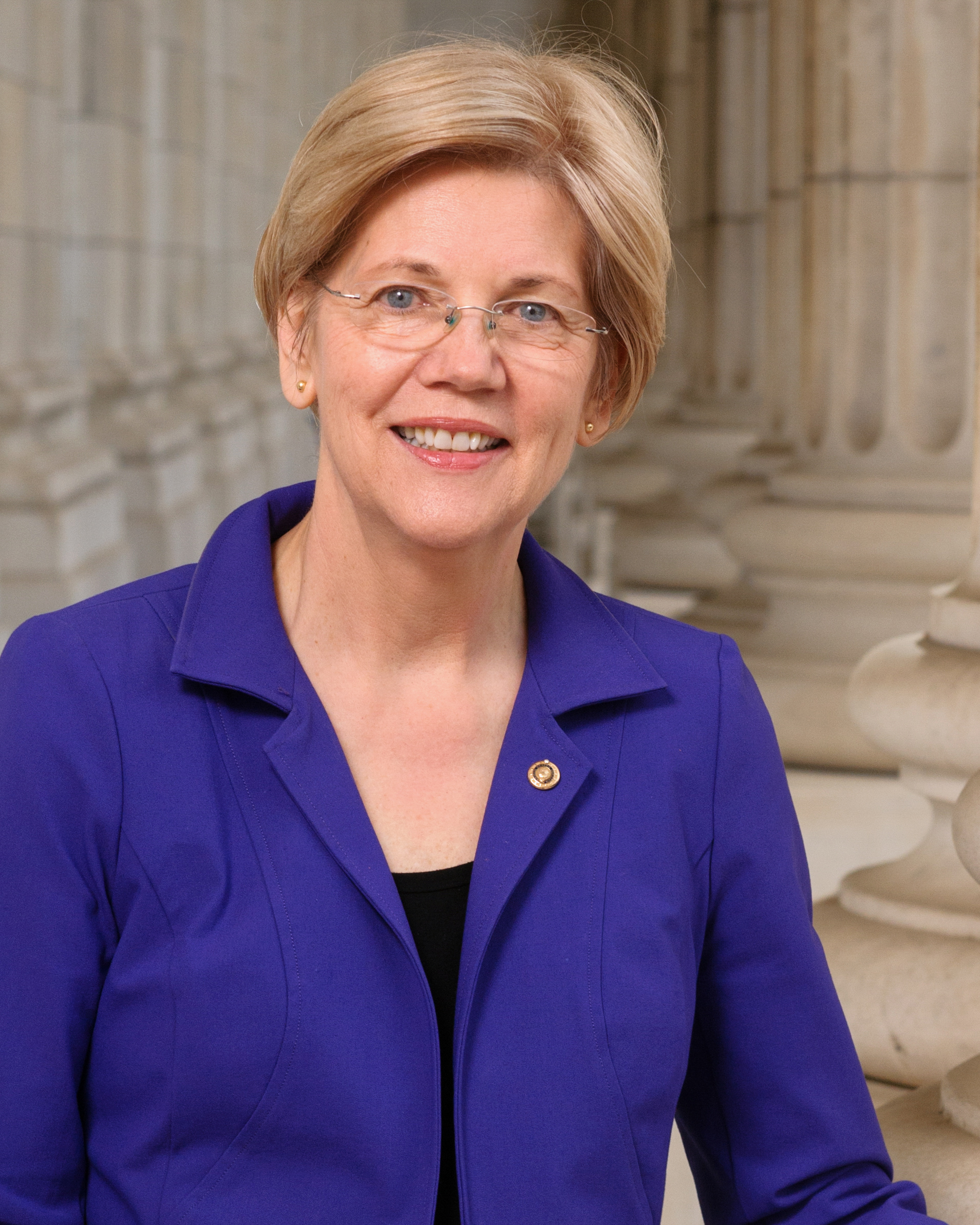

Warren performed poorly on Tuesday. She did not deny it in her final speech in New Hampshire, nor did her supporters or surrogates. Poor showing, however, is an understatement. To claim that Warren’s campaign is experiencing anything short of an existential crisis would be delusional.

Since her hyacinth days in late October, her support has slipped in every conceivable demographic. Overall, she has tanked by 10 points in the national polls to a level where Bloomberg exceeds her on average. Warren’s failure in New Hampshire was especially devastating. Throughout late 2019, Warren was a frontrunner in the state and a shoo-in for the top three. From location, to demographics, to ground game, Warren had every conceivable advantage.

The more populous South of the state receives TV, radio, and print media from Warren’s native Massachusetts. Historically, this has given primary candidates a significant boost: from Dukakis to Kerry. Proximity gave her a name recognition advantage rivalled only by Bernie Sanders.

Although Warren does not have a single base of support, it is no secret that Warren has relied on three demographics: white, college-educated, and high median income voters. New Hampshire was a chance for her to impress. The state is 93% white, boasts the sixth highest median income, and is ninth in the country for percentage of college grads. It is clear that her message simply failed to convince: other candidates were able to consolidate their support and trounce her in every demographic.

Despite the advantages Warren had from the outset, she never took the win for granted. She invested time, resources, and staff – more than any other candidate. With double the campaign offices, and double the money raised in the state, Warren only managed half of the vote share of underdog Amy Klobuchar.

Considering the cards she was dealt, New Hampshire was an embarrassment. She leaves the state with no delegates, but many unanswered questions.

The Hillary Effect

One question to which Democrats are yearning for an answer is that of electability. Far from ideal, the concept has been derided for being coded, essentially penalising female candidates on “likeability” and downplaying their competence. Voters are unswayed by the problematic nature of the metric. Two thirds of those surveyed in Iowa and New Hampshire believed that beating Donald Trump was more important to them than any policy positions.

This should come as no surprise – Clinton’s defeat to Trump in 2016 sent a shock to Democratic politics from which they have not recovered. Now, Elizabeth Warren is paying the price.

From the onset, other candidates have attacked Warren for her “elite” background as a Harvard Law School professor. Her dedication to policy minutiae, a point of attraction for her core base, has only reinforced this sentiment in voters who see her as “schoolmarmish”. This has ultimately been reflected in weak polling numbers among white working-class voters in deindustrialised areas – the demographic that propelled Trump to the presidency in 2016. Her newest message of party unity is no better, bearing striking similarities to Clinton’s “Better Together”.

Moreover, a series of gaffes and poor decisions has led voters to mistrust Warren. The Native American DNA test raised concerns about her authenticity. Early on in the campaign came “I’m gonna get me a beer”, followed some months after by an awkward appearance on Stephen Colbert. In the eyes of many voters, this has made Warren an easy target for Trump’s attacks. Others, especially on the left of the party, saw her as too much of a “politician” – especially given doubts lingering about her anti-establishment policy positions.

Indeterminacy on healthcare – a key issue in the Democratic primary – proved most harmful. In an effort to appeal to the progressive wing of the party, she began to advocate for a single-payer system, despite previously supporting a less ambitious plan. The only other candidate to support single-payer – Bernie Sanders – unabashedly declared that taxes on the middle class would rise under such a plan. Pushed on the same point, Warren floundered. Eventually, she released a plan that would cover the expansion in cost without raising taxes on the middle-class, one that was rapidly derided for being unrealistic. The saga hurt her credibility and increased perception of her as a calculating, establishment politician as opposed to an outsider.

In all likelihood, a similar series of step-ups by a male candidate would have flown under the radar (cf. Joe Biden). In many ways, Warren’s downward spiral is unfair. Nonetheless, Warren is falling to the same curse that befell Hillary Clinton – she is seen as unrelatable, and, ultimately, unelectable.

Life Support

In a memo released just before the New Hampshire results, Warren’s campaign manager Roger Lau claimed that the muddled race remains wide open, with Warren best placed to emerge victorious by the time of the Convention.

Essentially, Roger Lau’s message focused on Super Tuesday and her (somewhat) competitive polling numbers in delegate-rich states, combined with internal projections. He argued that Bernie has a “ceiling” that will prevent him from reaching plurality, that Biden’s campaign is on the ropes, and that Buttigieg will struggle in more representative states.

There is merit to some of Lau’s points, but, digging deeper, his claim that Warren has a shot at the nomination appears strained.

The fact remains that she does not lead a single state in the polls. There is no indication of momentum going forward, and other candidates are leading in almost every key demographic. Despite having pitched herself as a unity candidate, she does not command significant support from either wing of the party. Sanders has established himself as dominant among left-leaning democrats, while Buttigieg, Biden, and Klobuchar vie for the moderate vote.

Lau highlighted that the early races are unrepresentative of the country. For Warren, this is no curse. Among non-white voters she has fledgling support compared to Biden, Bloomberg, and Sanders. CNN’s exit poll on Tuesday had Sanders with 42% support among Latinx voters, compared to Warren’s 3%. A recent Quinnipiac University Poll showed Warren with 8% support among black voters, far behind Sanders’ 19% and even further behind Biden’s 27%.

The disastrous result in New Hampshire will make fundraising more difficult. Overturning early setbacks with a strong result on Super Tuesday will require extensive resources which Warren does not have. Sanders, who continues to lead in fundraising, and Bloomberg, who can rely on his unlimited cash reserves are likely to outspend in all key states and build on their growing momentum.

Elizabeth Warren entered the race with “a plan for everything”. As things stand, she has no plan for winning the Democratic nomination.

N.B.: When referring generally to nationwide polls, reference is being made to Five Thirty Eight’s poll averages.