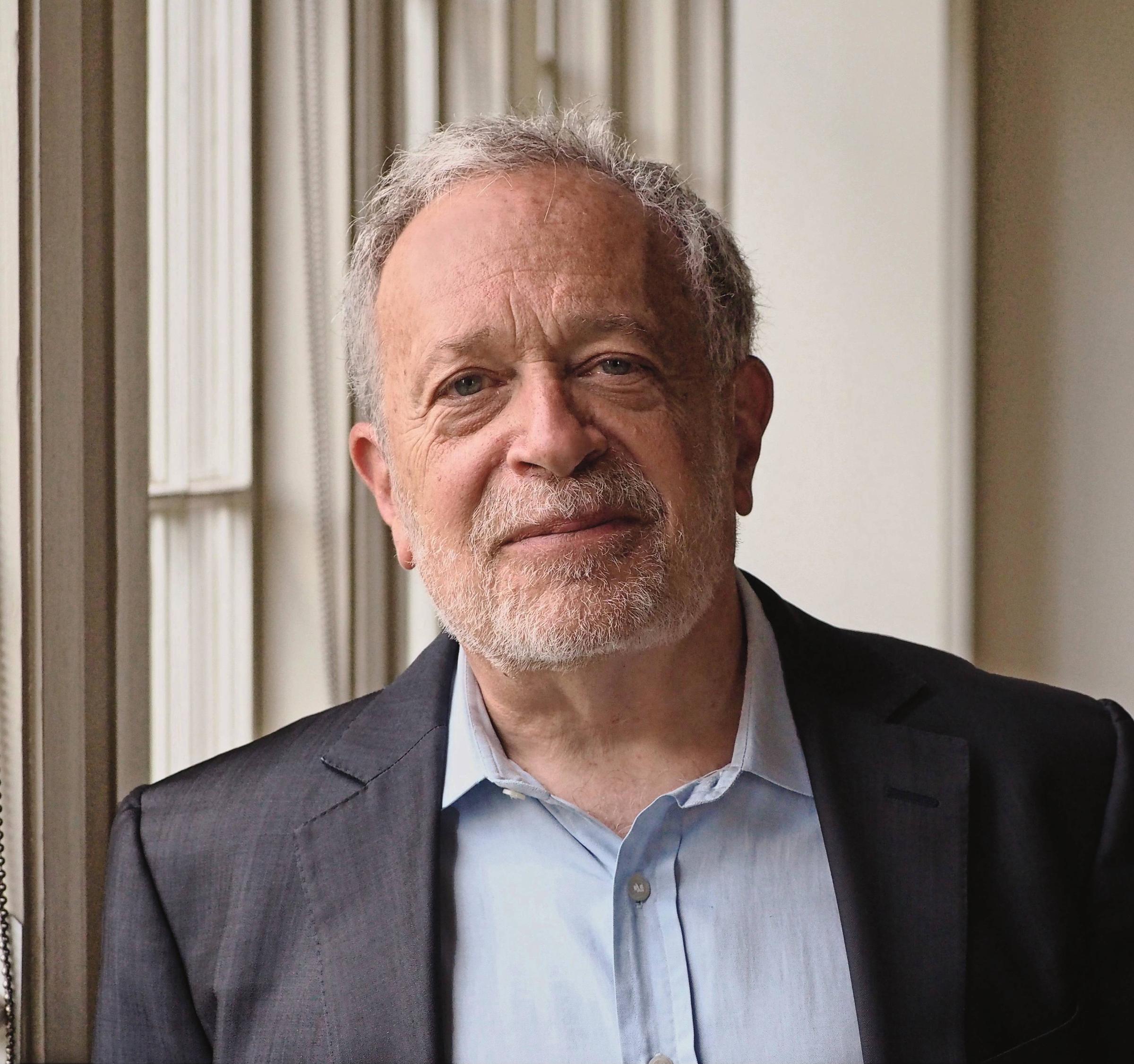

The Oxford Political Review speaks with Robert Reich, former US Secretary of Labor during Bill Clinton’s administration, leading labour economist, and current Chancellor’s Professor of Public Policy at the University of California at Berkeley and Senior Fellow at the Blum Center for Developing Economies. In the interview, Editor-in-Chief Brian Wong and Robert Reich discuss the future of labour, the left’s ability to reclaim and resist populism, the Democratic primaries, and on Robert’s greatest regrets with regards to his office.

BW: Where do you think the mechanisation of labour is taking us in the next decade – and, without pontificating over a crystal ball, what do you see as the next major trend in labour economics by, say, 2030?

RR: Technology has been replacing jobs forever, but no matter how far it advances I doubt it will be able to provide personal attention, personal touch, and personal service of a kind that people want and are willing to pay for. That’s where most of the jobs of the future will be found. But because such personal work won’t be very productive, it won’t pay much. Hence, the problem won’t be the number of jobs, but how much jobs pay. We won’t have a jobs crisis; we’ll have a good jobs crisis. An economic and political challenge will be to find means of recirculating money from those who own the intellectual property underlying the inventions that will be replacing good jobs, to the vast majority who would like to buy those inventions but will lack the money to do so.

BW: I am a massive fan of what you’ve said about the need to resurrect the “common good” in politics in your works. Do you think Clinton’s failure in 2016 largely stemmed from her inability to include the “Other” to progressivism – those whom she chastised as “the Deplorables”? How, if at all, do you think progressives ought to overcome the potential hamartia of becoming too insulated and disconnected from the working-class masses?

RR: Most Americans, like most citizens of the UK, haven’t had much of a pay raise in decades. Jobs are less secure than ever. Job benefits are shrinking. So it’s no surprise that large numbers of people feel the game is rigged against them, and they want to shake up the system. Clinton was indelibly part of the establishment. She won the popular vote by 3 million, but would have done far better, and defeated the moron we now have in the White House, had she convinced voters she’d embrace the sort of bold reforms Bernie Sanders advocated during the 2016 Democratic primaries (and still is in the 2020 Democratic primaries). Bernie and Elizabeth Warren are taking positions in the current primaries and evincing the kind of indignation that progressives must project if they are going to reconnect with the working class.

BW: Donald Trump is the epitome of big money, big corporations, and (very) big businesses. What do you think contributed to his ascendancy, and – despite his unprecedentedly low polling ratings – many are putting bets on his winning in 2020. How could Democrats work together to prevent this?

RR: Trump continues to convince 36 percent of America that he’s not the establishment. He does this by being blatantly “politically incorrect,” saying things that politicians don’t say, and acting as if he’s shaking up the old order. Most of his followers don’t know he’s actually shilling for billionaires; they haven’t followed or have been misled about his giant tax cut for big corporations and the rich; and they don’t know how much they’ve been hurt by his deregulatory and trade policies. Undoubtedly some of them share his bigotry, but a smaller portion than is commonly assumed. Democrats obviously shouldn’t imitate Trump’s racism and xenophobia, but they should advance a different sort of patriotism — one based on the common good, on public investment, in the goals of equal political rights and equal opportunity. They should talk about what we owe one another as members of the same society.

BW: The US has historically been criticised for its alleged warmongering tendencies – irrespective of partisan stances. Yet in 2020, a year when previously seemingly dormant geopolitical actors have become increasingly restless (I’m thinking North Korea and Iran here, whose belligerence has only increased after the falling-through of the Iran Deal), do you see these allegations as fair, and what do you think the American role to play internationally should look like?

RR: I do think those criticisms are fair, particularly when it comes to Trump — as evidenced by Trump’s withdrawal from the Iran nuclear agreement, culminating with his assassination (and that’s what it was) of Iranian general Soleimani. The great irony is Trump’s curious eagerness to do whatever Putin wants him to do. Republican ideas about foreign policy have taken a 180 degree turn under Trump, so that we now have Republican senators defending Russia and Putin. I’m a great believer in the American role of seeking to be a model of democracy for the rest of the world, using its moral authority to coax other nations in the direction of democracy, and its so-called “soft power” to defend itself wherever possible.

BW: China has been accused of violating core anti-competitive and copyrights protection laws. Yet in its defense it has argued that its pursuit of such measures – even notwithstanding condemnation by the WTO – is well-justified given the historical exclusion and disadvantage that it has been placed under. What are your thoughts on this?

RR: China has a point. After all, America’s manufacturing prowess was built on mercantilist tariffs and other measures to keep more superior British manufacturing at bay while stealing as much of Britain’s intellectual property as possible. But this whole line of argument fails to recognize the huge achievements China is making on its own in a range of industries of the future, including renewable energy. The United States is investing far less, as a percentage of its GDP, in basic research than is China, and than the United States did twenty years ago. We shouldn’t condemn China for having an industrial policy geared to the future. America’s industrial policy — subsidies, tax breaks, bailouts, and the like — are geared to industries of the past, such as oil, gas, and agriculture, or to finance. We need an industrial policy geared to the future.

BW: The intuitive issue with a Universal Basic Income (UBI) isn’t so much that it gives to the most vulnerable, but that it seems to also reward those who neither need nor deserve the safety net – obviously we should agree that maintaining a robust safety net is crucial, but could a better alternative to UBI not be to reform our welfare system for the better, so as to ensure that few folks slip through the cracks (but also that we do not give well-off middle-class and billionaires extra income)?

RR: There are many different versions of UBI. The one I favor is quite close to what we call the Earned Income Tax Credit, in that it would be a subsistence wage for people unable or unwilling to get a job that paid more — just enough to keep them out of dire poverty. Once someone has a job that pays above this subsistence level, the wage subsidy would be reduced. As the job paid more, the subsidy would phase out. This seems to be entirely sensible and necessary, particularly as automation and artificial intelligence depress wages (see above).

BW: In The Common Good, you argued that America’s national identity ought to be and should be founded upon a basis of equal political rights and opportunities for all to pursue what they deem to be the good life. I’m reminded of Ta-Nehisi Coates’ powerful article on the case for reparations in The Atlantic in 2014 – and was wondering, might this conception/imagination of the American identity not be a tad idealistic and detached from its historically and culturally colonialist connotations? Obviously, we could reclaim and re-interpret the American identity, but I do think we should be wary of whitewashing the identity’s historical legacy and heritage.

RR: Yes, of course it’s idealist. That’s the point. America’s founding fathers were white male oligarchs. But they harbored enlightenment ideals about equal political rights and equal opportunity that took seed in America in the late eighteenth century. Although never fully achieved continue to be guiding lights. We can, and should, both own up to our historical legacy of racism, misogyny, and xenophobia, while at the same time seek to move closer toward those ideals. That striving is what Abraham Lincoln, among others, saw as the core of our national identity.

BW: What is something you regret with regards to your tenure as Labour Secretary? What would be, if at all, your biggest criticism of the Clinton administration?

RR: I really should have fought harder against the financial types who argued ceaselessly that the Clinton administration couldn’t make the investments in education, job-training, basic research, and infrastructure that Clinton had campaigned on because we had to bring down the budget deficit. It was rubbish then and it’s rubbish now. I tried my best, but I should have banged my fist more times on more tables.

BW: Since your 2004 Reason: Why Liberals Will Win the Battle for America, I was wondering if your personal experiences over the past two decades have led you to revise any of the conclusions you outlined in that book – or if your conception of the best, most ideal strategy ahead for progressives has remained largely the same.

RR: I don’t recall what I advised in that book, but I don’t think my overall views have changed substantially. Progressives must understand — and educate others — that the real political divide is no longer left versus right, as it was understood in the first four decades after World War II — a contest between those who want more limited government versus those who want more active government. The new divide is between oligarchy and democracy — between a small minority of exceedingly wealthy people and the institutions they lead (large corporations, hedge funds, private-equity firms, and big banks), on the one hand, and the vast majority of people who continue to struggle to get by, and who have no real voice.

BW: Do you think the Dodd-Frank Act has done more to fix the endemic problems within highly deregulated financial markets, or instead exacerbated and entrenched the oligopoly of a few regulation-savvy behemothic firms? What would be your equivalent to a “Dodd-Frank”, if any, for the American labour markets?

RR: Dodd-Frank is almost a dead letter. The biggest banks and financial institutions have watered it down so much that many of them are back to the old tricks that brought the economy to the edge of catastrophe in 2008. The biggest banks constitute an oligopoly, but not because of Dodd-Frank. It’s because they got bailed out by the government in 2008, and now they’re now indubitably too big to fail. They in effect enjoy a federal guarantee that whatever they do they’ll be bailed out. The imputed value of that guarantee has been estimated to be well over $58 billion a year to the five largest Wall Street banks.

BW: The American education system seems broken – and is threatening the very human capital upon which the country is built. How can we fix it?

RR: We should invest considerable sums in early-childhood education. We should no longer rely on local property taxes to finance our primary and secondary schools (as Americans segregate into different school districts according to income, this has had the perverse result of causing poorer populations of children to have far lousier schools). We should create a world-class system of technical education, centered on our community colleges. We should subsidize the costs of university education for anyone who needs it, and stop piling on student debt. Most importantly, we need to restore the idea that education is a public good, not a private investment.

BW: How do you find your current work as Professor of Public Policy? What is your next big project that we could look forward to hearing about?

RR: I love it. I love teaching. Berkeley is a fabulous university with wonderful students. I enjoy my research and writing. And I’ve been spending some of my time doing videos on various issues of political economy. (You can find them on the website of Inequality Media, which I co-founded.) My next book, due out March 26 in America and May 26 in the UK, is called “The System: Who Rigged It, How We Fix It.” I hope you read it.

BW: Do you not think that the “1% vs. 99%” rhetoric – whilst viscerally effective in encapsulating the disparities in our society today – perhaps is also unhelpfully antagonistic in a way that alienates those whose support we both need and would benefit from in order to reform the broken capitalist system?

RR: At first I did, but I’ve found that it clarifies for many people the astounding degree of inequalities of income, wealth, and political power now infecting the United States as well as other so-called advanced nations. I tend to speak more about the “0.1%” rather than the “1%” because the nexus of wealth and power is far more evident at that level, and even more obvious at the level of the “0.01%.”

BW: Do you think it’s high time that we abandoned capitalism? Is socialism compatible with the constantly appropriating, never-satiated telos of capitalism?

RR: These terms aren’t helpful. I believe we need to have far stronger safety nets and far more public investment in education, health care, basic research, and infrastructure. I believe we need to tax great wealth in order to pay for much of this. I believe we need to get big money out of our democracy in order to enact any of this, and give average people more of voice and agency. If we do all these things, we will achieve a great deal. If we don’t, I fear increasing public discontent fueling more Trumpian authoritarianism, xenophobia, and racism.