In the opening scene of I, Robot, a terrifying car crash throws Chicago police detective Del Spooner (played by Will Smith) and a 12 year-old girl into the nearby ocean. A passing robot, through a brute calculation of odds, dives in to save Del’s life at the expense of the child’s. The experience instils Del with a permanent distrust for robots — a distrust that proves prophetic in the course of the film. Del is an allegory for Western man and his complex relationship with technology; the robot saved a life, but arguably the wrong one. For the West, technology will save man, just not the way man intended.

Distrust of technology runs deep within the Western literary canon. In Plato’s Phaedrus, the art of writing (an ancient technology), initially deemed an aid to memory, is seen as a harbinger of forgetfulness. Marxists tend to be sceptical about the emancipatory potential of technology given the way it has enabled oppressive social relations under industrial capitalism. Foucault and his postmodern predecessors are known for their critique of disciplinary technologies: the mechanisms, procedures, architectures, and tools used to discipline members of modern societies. Today, the West is in the midst of a technological reckoning with social media sites and their implication in privacy violations, electoral interference,data breaches, and political radicalisation. From Ancient Greece to the Digital Age, technological scepticism has been the predominant ethos of the West.

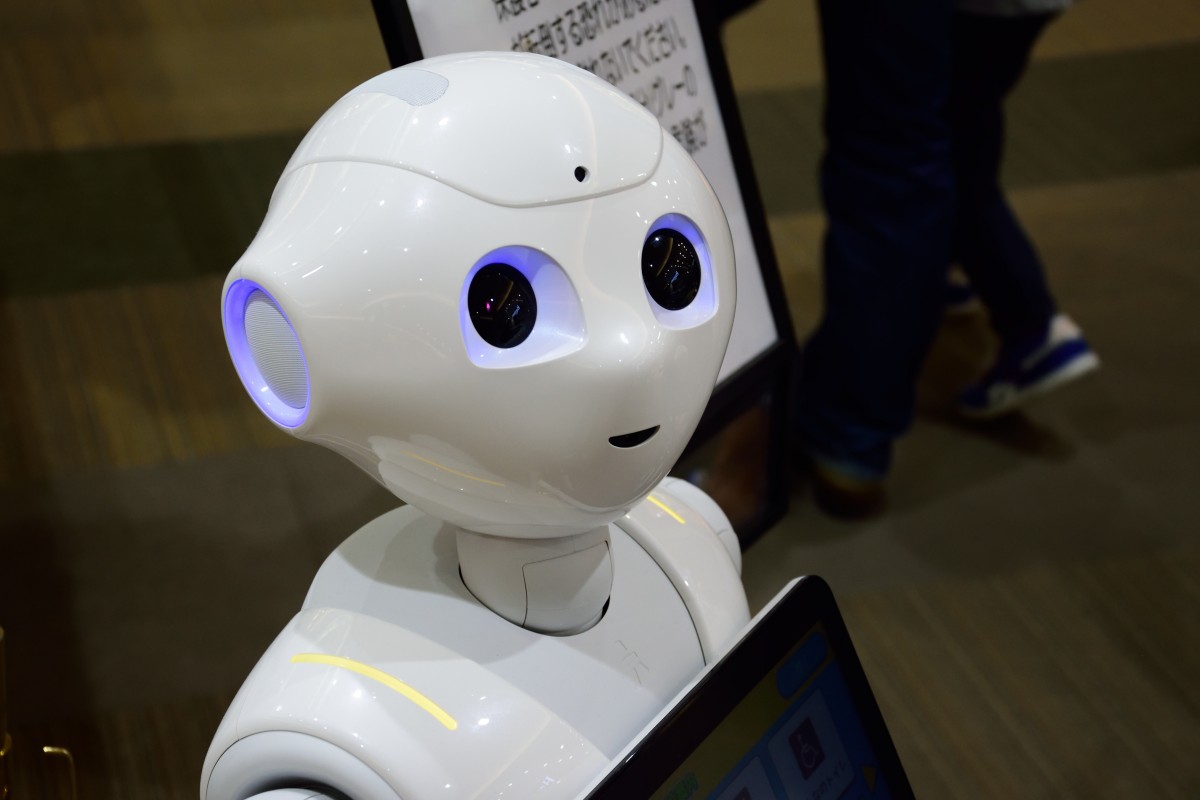

Particular noteworthy amongst the many puzzling philosophical differences between Japan and the West is their relationship to technology. Hollywood sci-fi films such as theMatrix, The World’s End, and Terminatortend to depict robots as humanity’s natural enemy; each group’s survival entails the other’s destruction. Yet this adversarial arrangement of the man-machine binary is strikingly absent in the cultural products of the small island country. When robots do appear in Japanese media, they are companions rather than enemies. And, when Japanese animators project into the future, robots are integral members of that future, not its primary obstacle. The Japanese see technology not as a threat to humanity but an extension of its will. This may explain why one of the country’s most successful anime franchises touts a main character that is not even human. Since its serialisation in 1952, the Astro Boy series has made over $3 billion in merchandise sales making it one of the highest grossing media franchises in the world. The show’s titular hero, however, defies any storytelling logic of the West; he is a robot who fights human villains.

The Western propensity to view robots as humanity’s antagonists, caught in a zero-sum game for survival, is no accident. It is a manifestation of philosophical paradigms that have fundamentally affected the way we take in and interact with the world — an ideology of sorts. This ideology — the inherent dualism of the conqueror and the conquered — can be uncovered in much of Western philosophical history. It can be traced back to the ideals of the Enlightenment, whose conceptions of scientific progress necessarily viewed nature as that which must be subjugated, tortured, and controlled. It can also be found in conceptions of private property that elevated the status of some individuals to that of property owners and consigned others to that of property. It is no accident that modern capitalism cannot help but conceptualise market interactions as producing winners and losers. Today, to say “all men are created equal” or that “the individual is the fundamental unit of moral concern” is to offer nothing but a platitude. It is an unfortunate reality that, historically, those deserving of rights have come only at the expense of those who did notdeserve them. Conceptions of “man” have always been tenuous and contested in western philosophy.

By consequence, popular movies such as I,Robotportray their mechanic characters in accordance with the Hegelian master-slave dialectic. They serve as the new counterpoint to our “modern” conception of “man” and the subsequent rights that are guaranteed by them — today, we are man because we are not machine. History may not repeat itself but it will rhyme. And so, oppressed robots instil in the Western psyche a fear of being overthrown just like slave revolts did in the past. This inherent dualism has remained hopelessly consistent throughout western history: no matter how many different ways its content has been filled in centuries prior (man-woman, white-black, man-machine), its fundamental logic has remained untouched.

If the West’s conception of robots in dialectical terms can be traced back to its philosophical traditions, then in Japan, the bedrock of Shinto religion, something altogether different must be generating the collaborative image of man and robot. In Japanese, the term for “human” ningen (人間), contains both the character for “person” and the character for “space” or “in-between”. Hence, to say “man” in Japanese is not to refer to a distinct, atomistic individual, but rather the connections and relationships that people form as they interact with each other; “humanity” is made up not so much by individuals, but their interrelations.

The intersubjective nature of the Japanese word for “man” is indicative of a morality that is not grounded in any specific kind of dualism (between what one considers “man” and “non-man”) but rather a spiritual holism that is all-inclusive. In this moral system, humans are not special—ownership is not an active privilege granted only to “man” but a passive state of being shared by all: “Nature doesn’t belong to us, we belong to Nature, and spirits live in everything, including rocks, tools, homes, and even empty spaces” wrotedirector of the MIT Media Lab Joi Ito. This unifying conception of the world also draws from the Japanese aesthetic concept of mono-no-aware(translated as “the pathos of things”): a philosophical view grounded in the impermanence of life. No object, human or non-human, is spared from impermanence. Robots are, just like humans, rocks, insects, and trees, a part of the world living together in harmony, awaiting an inevitable finality.

Systems of thought cannot be fully reduced to an East and West dichotomy. Yet it is undeniable that inhabitants of different regions carry with them culturally specific paradigms that help interpret their surroundings, particularly in the face of new challenges. This method of allocating new data into pre-existing frameworks may have been integral for the survival of our ancestors, but it can be dangerous when carried over to the sheer magnitude of modern problems. Artificial intelligence, for example, is a new global challenge that cannot be subsumed under traditional paradigms — a problem that calls for what behavioural economists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky call “slow” rather than “fast thinking”. That is, as AI becomes more and more sophisticated, it becomes all the more pressing to revisit our inherited cultural priors that risk placing new challenges into old frameworks. In the Genealogy of Morals, Nietzsche offers one way out of our inveterate cultural priors: an exploration of the past that seeks to both estrange and provide the conditional basis for our present systems of values. But if estrangement it what is necessary to tackle our out-dated cultural ideas, then a cultural comparison is equally effective. That is, studying alternative cultural traditions can enable the same kind of critical reflection and possibility that inhere in genealogical analysis. In the case of technology, cultural comparisons provide the much-needed conceptual tools to rethink each region’s relationship with machines.

In the West, one lesson from engaging in dialogue with the East is to rethink the robot revolution narratives that dominate public discourse. The outsized number of tech leaders suggesting AI will take over the worldfalls perfectly into the Western narrative of domination and subjugation. In reality, the central concerns of an AI integrated world is much more subtle and complex than any dichotomous framework of power struggle. Doing away with this dialectical thinkingmay enable more thoughtful and complex engagement with problems of more pressing concern, such as AI’s uneven impact on the economy, where AI has replaced human work, and how best to distribute its economic benefits. The view of AI as contributors to human flourishing will become pivotal in the coming decades. As AI leads to mass unemployment, societies will be pushed to subsidise jobs that are currently underpaid by the labour market (those such as coaching, tutoring, mentoring, and parenting). In this new world, companies who continue to hold a capitalistic view of technology as a tool to maximise profit will see no obligation to redistribute their AI profits to unemployed workers. On the other hand, a collaborative view of AI may encourage AI companies to see their profits as tied to the future of work. Those profits may then fund new sectors previously undervalued by the labour market. Toward this end, Joi Ito has begun advocating for a reconceptualisation of artificial intelligence as Extended Intelligence (EI). In EI, artificial intelligence is not a tool for improved efficiency but a companion for human self-understanding and the reaffirmation of human values.

But cross-cultural lessons can cut both ways. As Japan begins to ramp up automationto address its labour shortage problem, Japanese technologists can learn a great deal from the predominant narratives of AI in the West. First, automation can change the job landscape in a matter of decades. Due in part to technology, the US is presently undergoing a major shift from manufacturing jobs — which declined by five millionsince the year 2000 — to sectors like nursing, caregiving, retail and operations. Such changes correspond to changes in the skills that workers need to partake in the economy. Japan has already undergone this transition: manufacturing jobs were at a 50-year lowin 2012. Now, automation is becoming a major solution to address labour shortages in the service sector, especially in nursing and social carewhere robots have already been deployed in Japan by the thousands. In the long run, jobs in these key sectors will be replaced and Japan will experience a decline in service work much like the country’s earlier decline in manufacturing. The government must have a contingency plan for identifying high growth sectors (provided they exist) and easing the shift of workers from the sectors they replace to those new ones.

Second, the jobs threatened by automation are concentrated amongst the most vulnerable to change: lower-paid, lower-skilled, and less-educated workers. This is true in both the US and Japan, which means that increased productivity from automation is not distributed to those whose jobs they have replaced. The Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) recently estimated that the market for nursing care and disabled aid robots is projected to grow from just $19.2 million in 2016 to $3.8 billion by 2035. Those who will reap the benefit of this growing industry will not be blue-collar workers but technology companies. In the coming years, Japan will have to fill the labour shortage gap using creative measures including open immigration policy, female empowerment in the workforce, and automation. Yet improved productivity from automation is different from the other solutions in that it does not correlate directly with wage growth. Therefore, as Japan invests heavily into automation, its government must work to ensure that the prosperity from automation can also be shared for workers and consumers so as to prevent a reduction in competition and increased wealth inequality.

Ozamu Tezuka, the creator of Astro Boy, once said in an interviewthat the view of AI in Japan is one of “no resistance” and “quiet acceptance”. This view, coupled with the current shortage in labour, often makes automation seem like a panacea for the Japanese in the midst of their “national crisis”. But Western experience has shown that technology is a double-edged sword: it saves us in a time of need but leaves us in a new predicament; the current social media crisis in the US is this principle par excellence: it has brought us together in one sense, but has also split us apart in another. Because of its unprecedented economic and social challenges, Japan is becoming a test case for the world’s interest in addressing their own hyperaging societies. By investing heavily in automation as a solution, Japan has also become an experiment in how robots can best be integrated into the economy. In the midst of this technological upheaval, it could use a healthy dose of Western robot scepticism and prepare for the effects of using automation to address labour shortages.

The philosophical divide in conceptions of technology serves as a stark reminder that our perceptions and intuitions can benefit from alternative cultural viewpoints. Just as David Foster Wallace’s young fish in his famous speech “This is Water”does not recognise the water he relies on to breathe, we who inhabit a specific culture do not always notice the cultural eccentricities of our most natural tendencies. By inhabiting other cultural perspectives, we can take notice of deeply held assumptions, bringing them into a new light so that they can be re-examined. This re-examination has become increasingly more pressing. Contrary to nationalist sentiments across the globe, challenges surrounding climate change, technology, immigration, and aging populations require cross-cultural dialogue and innovative solutions. By suspending our initial intuitions about AI — specifically, where it should or shouldn’t be deployed — we might expand the horizon of possibilities for AI in favour of smarter domestic solutions. We might do well to understand the water we breathe, so that we’re well prepared when the tides inevitably change.